Joachim, Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus' (Savelov Ivan Petrovich). Modern problems of science and education From monk to metropolitan

Patriarch Joachim (in the world Ivan Petrovich Savelov the first; January 6, 1621, Mozhaisk - March 17, 1690, Moscow) - the ninth and penultimate Patriarch of Moscow in the pre-synodal period (July 26, 1674 - March 17, 1690).

Patriarch Joachim

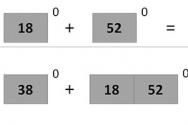

Shilov V.V. Portrait gallery of the Patriarchs of Moscow and All Rus' Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus' Joachim. 1674-1690

Biography

He came from a family of Mozhai nobles, the Savelovs; one of the ancestors at the end of the 15th century was a Novgorod mayor. In 1655, he left military service and became a monk, joining the ranks of the monks of the Kiev-Mezhigorsky Monastery. In September 1657 he became a monk, and soon the “builder” of the Valdai Iversky Monastery. In 1661, the disgraced Nikon transferred him to the position of “builder” in his New Jerusalem monastery. Soon Joachim became a cellarer at the Novospassky Monastery. In 1664, upon the appointment of the Chudov Archimandrite Paul to the see of Metropolitans of Sarsk and Podonsk, he was appointed archimandrite of the Chudov Monastery, as a result of which he became in close relations with the court and with Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich himself. He also became close to Colonel Artamon Matveev. In 1672 he was appointed metropolitan of Novgorod. He introduced a certain church tribute in his diocese, uniform for everyone, abolished the custom of sending secular officials who committed abuses from the metropolitan order to collect this tribute, and ordered the priestly elders to collect this tribute.

On July 26, 1674 he was enthroned as the Moscow Patriarchs. He was titled “By the Grace of God, Patriarch of the reigning great city of Moscow and all Russia.” Soon after ascending to the primate see, he issued a direct challenge to Alexei Mikhailovich: in November 1674, he arrested and put in chains the royal confessor Andrei Savinov; the tsar was forced, in view of the undeniable evidence presented against the archpriest, to ask Joachim not to transfer the confessor’s case to the court of the Consecrated Council. At the beginning of the reign of Theodore Alekseevich he was among the de facto rulers of the state along with Ivan Miloslavsky.

At the end of April 1682, he was at the head of those who carried out a palace coup, as a result of which the younger brother of the late Theodore Alekseevich, Tsarevich Peter Alekseevich, was declared tsar. On June 25, 1682, he crowned Peter and his older half-brother Ivan Alekseevich to the throne. In 1686 he applied for a royal charter stating that clergy would not be subject to the jurisdiction of civil authorities. In 1687 he established a common standard for church tributes and duties for all dioceses.

He decisively opposed plans for the coronation of Princess Sophia, which gave rise to a plan among her party for the deposition (and even murder) of Joachim and the elevation of Sylvester Medvedev to the Patriarchal throne. During the events of August 1689, he actually took Peter’s side in his confrontation with Sophia, remaining with him in the Trinity Monastery.

Fighting the split

The Council of 1681 recognized the need for a joint struggle between the spiritual and secular authorities against the growing “schism”, asked the Tsar to confirm the decisions of the Great Moscow Council of 1667 on sending stubborn schismatics to the city court, decided to select old printed books and issue corrected ones in their place, established supervision over the sale of notebooks, which, under the guise of extracts from the Holy Scriptures, contained blasphemy against church books.

(rokbox title=|Dispute about faith| thumb=|images/2-3.jpg| size=|fullscreen|)images/2-3.jpg(/rokbox)

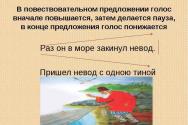

Vasily Perov. "Nikita Pustosvyat. Dispute about faith." 1880-81. (“debate about faith” on July 5, 1682 in the Faceted Chamber in the presence of Patriarch Joachim and Princess Sophia)

Patriarch Joachim took every care to ensure that the decrees against schismatics did not remain a dead letter: in these particular types, the number of bishops’ sees was increased and those bishops who had until then lived in Moscow were sent to their dioceses with the aim of correcting schismatics “through prayer and teaching.” He sent special exhorters to larger centers of schism and published a number of polemical anti-schism works. Along with smaller works against the schism, such as: “Notice of a Miracle” (M., 1677), “On the Folding of Three Fingers” (M., 1677), “Instructions to All Orthodox Christians” (M., 1682), word gratitude “On the deliverance of the church from apostates” (M., 1683), “The Word against Nikita Pustosvyat” (M., 1684, 1721, 1753), Joachim is also credited with “Spiritual tribute” (M., 1682, 1753 and 1791) - an extensive work that was written on the occasion of the riot of 1682, in response to the petition filed at that time, is still recognized as one of the best works against the schism. It is unlikely, however, that it actually came from the pen of Joachim, although it was published in his name. The entire essay was written in 50 days - a period too short for the patriarch, burdened with complex administrative affairs. The author of “Uvet” shows a deep understanding of the schism and a good polemicist, while Joachim was neither one nor the other; During the debate between the schismatics and the Orthodox in the Faceted Chamber on July 5, 1682, the main character on the part of the Orthodox was not he, but Athanasius, Bishop of Kholmogory and Vazhesky. “Uvet” consists of historical and polemical parts. The first outlines the matter of correcting church liturgical books under Nikon and proves its legality. The second part answers in detail the points of the schismatic petition, confirming its opinions with extracts from ancient books.

State of the Russian Church

During the patriarchate of Joachim, the following new dioceses were established: Nizhny Novgorod, Ustyug, Kholmogorsk (Arkhangelsk), Tambov and Voronezh.

The Council of 1675 in Moscow established the exclusive jurisdiction of the church court over the clergy. The Council decided that diocesan bishops should have clergy judges on their orders, that secular judges should not judge or administer anything to clergy, that church tributes should be collected by archpriests, archimandrites or priestly elders, that nobles and boyar children would be sent of the bishop's orders only “on disobedient and disobedient people.” The Council abolished the custom of summoning to Moscow, based on petitions from Moscow people, those persons of clergy who did not belong to the Patriarchal region; The source of bishops' bickering and self-will was also destroyed, which consisted in the fact that some church estates were subject not to those bishops in whose dioceses they were located, but to others.

At the council of 1675, the official (servant) of the bishop's ministry was also considered; Strict regulations were issued against luxury in the clothing of the clergy. In 1677, the Monastic Order was abolished.

The Council of 1682 considered questions about measures against schismatics, and also discussed the tsar’s proposal to divide the Russian Church into 12 metropolitan districts and open 33 dioceses, but the project was not accepted by the episcopate, which saw it as a threat to its powers and income. In the fall of 1686, the Kiev Metropolis was subordinated to the Moscow Patriarchate.

After preliminary review and correction, the following liturgical books were published: Trebnik (1680), Psalter (1680), General Menaion (1681), Octoechos (1683), Book of Hours (1688) and Typikon (1682). The Apostle was also corrected, but apparently was not printed.

In the 1680s, the “Latin” practice of performing “divine adoration” of bread and wine during the liturgy, which came from Little Russia, spread in Moscow until they were recited in the sacrament of the Eucharist. The situation apparently was taken advantage of by the Jesuits, who at that time received the right to open their own school in Moscow. Their supporters were Simeon of Polotsk and his student, the “builder” of the Zaikonospassky Monastery, Sylvester Medvedev; They were joined by some influential boyars who were part of the party of Princess Sophia. Joachim undertook a refutation of the teachings of the “pageants” by turning to the Eastern Patriarchs: the Patriarch of Jerusalem sent the Orthodox Confession of Peter Mohyla in a Greek translation. The Likhud brothers, who arrived in Moscow to organize teaching at the Typographical School (Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy), also took part in the dispute on the side of the Patriarch.

After the rebellion of 1689 and the execution of Theodore Shcheglovity, the Patriarch insisted on the expulsion of the Jesuits from Moscow.

In January 1690, a Council was convened, which anathematized the “bread-worshipping heresy”, heard the repentant confessions of Sylvester Medvedev and Priest Savva the Long, accused of the “bread-worshipping heresy”, as well as a “teaching word” on behalf of the Patriarch. The council condemned Medvedev's works to burning and forbade reading many works of southern Russian scientists “who are of one mind with the pope and the Western Church.”

To refute the teaching, Joachim also intended to publish the collection “Osten”, containing a refutation of the Latin opinion about the time of the transubstantiation of St. Gifts, compiled, on behalf of Patriarch Joachim, by Euthymius, a monk of the Chudov Monastery; but the death of the Patriarch on March 17, 1690, prevented this enterprise. In March 1681, by decree of the Patriarch, the Typographical School, which became the basis for the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy established in 1687, was founded by Hieromonk Timothy, an associate of the Patriarch of Jerusalem Dositheus, the first higher educational institution in Muscovy.

On October 24, 1688, Patriarch Joachim’s sister Euphemia Papina received healing from the icon of the Mother of God “Joy of All Who Sorrow” from the parish Church of the Transfiguration on Ordynka (now known as the Church of Sorrows). Currently, this is one of the few ancient miraculous icons preserved in Moscow in the 20th century.

Literature

P. Smirnov. Joachim, Patriarch of Moscow. M., 1885. G. Mirkovich. About the time of the transubstantiation of St. Darov. Vilno, 1886 Barsukov I.P. All-Russian Patriarch Joachim Savelov. St. Petersburg, 1890 Bulychev A. A. About the secular career of the future Moscow Patriarch Joachim Savelov // Ancient Rus'. Questions of medieval studies. 2009, no. 4. pp. 33-35

(Savelov Bolshoi Ivan Petrovich; 01/6/1621, Mozhaisky district - 03/17/1690, Moscow), Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus'. I. was the eldest son of the Mozhai landowner, the royal krechetnik Pyotr Ivanovich Savelov and Euphemia Retkina (Redkina) (in monasticism Eupraxia). In addition to him, the family had 5 children: Pavel, Timofey, Ivan Menshoy and 2 daughters, one of whom was named Euphemia. I.'s father belonged to the Mozhaisk branch of the Savelov family - hereditary masters of falconry; pl. I.'s relatives served as the sovereign's falconers: grandfather Ivan Osenny Sofronovich with his older brothers Fyodor Arap and Vasily, cousins Akindin Ivanovich, Grigory Fedorovich and Gavriil Vasilyevich, cousin Ivan Fedorovich.

When Ivan Bolshoy Savelov turned 14 years old, he had to enter the service. There is no documentary evidence of his career until 1644, when he received land plots in Mozhaisk and Belozersky districts as a sytnik. Apparently in mid. 30s XVII century Ivan Bolshoi either took up the family profession or became one of the palace servants. The latter is more likely, since his connection with the palace department can be traced through documents: in the royal letter dated September 2. 1652 in Mozhaisk voivode Prince. Y. Shakhovsky, regarding the endowment of I. Savelov with the barter estate “as before”, indicated the title of the latter - “The Feed Palace Solicitor of the Reitar System” (RGADA. F. 233. Op. 1. D. 64. L. 9-9 vol.). In con. 30s XVII century Ivan married Euphemia, “born and raised of pious parents,” and in his marriage he had 4 children, whose names are unknown. There is a hypothesis that the last 4 commemorations in the synod of the family of I. from Chudov in honor of the Miracle of the arch. Michael in Khoneh husband. mon-rya: Sophrony, Glykeria, Elena, Gury - refer to the children of the patriarch (Savelov L.M. 1912. P. 3. Note 3).

Among contemporaries there was a widespread opinion that I. learned to read and write only after becoming a monk, which gave rise to disparaging comments about the high priest (“Patriarch Joachim knows little about reading and writing”). However, in the Life of I. it is stated that in childhood, “when the time was ripe, I devoted it to learning to read and write, and by God’s grace studied the scriptures of book reading” (Life and Testament. 1896. Vol. 2. P. 3). According to widespread church tradition, I. studied at the Kiev-Mohyla Collegium (I.’s portrait was in the college among the portraits of famous students). However, no traces of Latin-Polish. the education that was instilled in the college is not in the views of the Greekophile I.; the patriarch was a sharp opponent of the Catholic Church. influence on the Orthodox Church Church. Apparently, as a child he received the usual for Orthodox Great Russians in the 17th century. disciplinarian education. There is reason to say that I. Savelov, during his life in Moscow, before leaving for military service, belonged to a circle of Hellenophile intellectuals grouped around mon. Epiphanius (Slavinetsky) and the okolnichy F.M. Rtishchev (it is known about the patronage of F.M. Rtishchev and his father M.A. Rtishchev I., when the latter lived in Valdai Svyatoozersk in honor of the Iveron Icon of the Mother of God mon-re, in Moscow monasteries -ryakh). Perhaps in Moscow I. Savelov acquired knowledge of Greek history. bookishness, it is possible that he received initial information about the Greek. language.

In 1649 or 1650, I.P. Bolshoi Savelov entered the Reiter service in the regiment of I. Fanbukoven (van Bukoven). This regiment was not so much a combat unit as a training center that trained Russian soldiers. serving people, officers of the army of the “new system”. Ordinary reiters of the Fanbukoven regiment retained their social status, remaining on the lists of institutions and corporations where they were before joining the regiment, and continued to receive salaries and “additions” there (see the already mentioned letter to the Mozhaisk governor, Prince Shakhovsky, dated September 2, 1652 ., as well as a letter to him dated October 7, 1652, where I.P. Bolshoy Savelov is named “Stern Palace Solicitor” (RGADA. F. 233. Op. 1. D. 64. L. 257 vol.-258 )). The younger brother and full namesake of the future patriarch I.P. Menshoy Savelov, who served in the reiters in the 50-60s. XVII century, also appears in the order documentation. But although by the beginning 50s both Savelov brothers were ordinary reiters; they had different local salaries: by the summer of 1651, the eldest was entitled to 200 quarters. land, the youngest - 350 quarters. I. P. Menshoi Savelov, a Mozhaisk nobleman “by choice,” in the import document dated June 1, 1654, was named as a serviceman of the “Reitar system,” while I. P. Bolshoy Savelov in the fall of 1653 already had the rank of officer. After the autumn of 1652, the name of I.P. Bolshoi Savelov, solicitor of the Feed Palace, is no longer found in the acts sealed in the Printed Order, while his younger brother continued to receive royal charters for land and ranks. Ivan Menshoi Savelov was promoted to captain in December. 1663, when his elder brother had already taken monastic vows.

In the fall of 1653, I.P. Bolshoy Savelov, among those who distinguished himself, received the rank of lieutenant. From that moment on, his service in the Feed Palace ceased and he found himself associated with the regiments of the “new system” and the Inozemsky order, which was in charge of the officer cadres of those regiments. On Nov. 1653 I.P. Bolshoy Savelov arrived in the foot soldier regiment of Colonel Yu. Gutsov (Gutsin). As follows from the salary sheet “Names of the initial people: captain, and lieutenant, and ensign, to whom to give the sovereign’s salary of food money for November, and for December, and for the January months of this year 162,” in the new service he was entitled to 3 rubles. 11 altyn “for a month” (RGADA. F. 210. Art. Moscow table. D. 867. L. 293; cf.: Kurbatov O. A. Organization and fighting qualities of the Russian infantry of the “new system” on the eve and during the Russian- Swedish war of 1656-1658 // Archive of RI 2007. Issue 8. P. 174). In 1654, a war began between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. 23 Feb Gutsov's regiment entered Kyiv and formed the basis of the city's garrison. On March 3 of the same year, a royal letter was entered into the notebook of the Printed Order to the Kyiv governors, princes F.S. Kurakin and F.F. Volkonsky: “Ivan Savelov was ordered to be in the sovereign’s service on foot in the Saldatsk formation in Yuryev, Guttsov’s regiment from lieutenants to captains to a retired (vacant - A.B.) place" (RGADA. F. 233. Op. 1. D. 71. L. 28 vol.). Together with Russian garrison I.P. Savelov quartered on Podol. In the 2nd half. In June 1655, Guttsov’s regiment left Kyiv, in July participated in the army of boyar V.V. Buturlin in the fighting in Right Bank Ukraine (History of Kyiv / Editorial volume. I. I. Artemenko et al. K., 1982. Vol. 1 : Ancient and medieval Kyiv. P. 368; Maltsev A. N. Russia and Belarus in the 17th century.

Soon, I.P. Savelov received news of the death of his wife and children (probably during the plague epidemic that swept through the central counties of Russia in the summer and autumn of 1654). A personal drama pushed him to accept monasticism, bud. The patriarch took monastic vows in the Mezhigorsky men's monastery near Kiev in honor of the Transfiguration of the Lord. The choice of the Mezhigorsk monastery could have been the result of a conscious decision. After many years of desolation, the Mezhigorsk monastery was restored in 1600 by Hierom. Afanasy Svyatogorets, who probably arranged it according to the Athos model. Later, the monastery was rectored (until his consecration to the Przemysl See in 1622) by a consistent fighter for the purity of Orthodoxy, Isaiah (Kopinsky). Having spent a “short time” as a novice, at the beginning. 1655 I.P. Bolshoy Savelov was tonsured into monasticism by the abbot of the Mezhigorsky monastery Varnava (Lebedovich) with the name Joachim, after tonsure he served as a cell attendant to the “reverent elder” priest. Marciana. In April 1657 Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich sent 100 rubles through the “elder” I. to the Mezhigorsky Monastery and 50 rubles. to the Krekhov Monastery, Lviv povet. Until the end of his life, I. recalled with gratitude the place of his tonsure. In addition to generous donations, he donated stauropegy to the monastery and even dreamed of being buried in it (Savelov L. M. 1912. P. 63; He. 1896. T. 2. P. 35).

On Sept. In 1657, by letter of Patriarch Nikon I. was transferred to the Valdai Svyatoozersk Monastery. The Life of I. reports his appointment as the builder of the monastery. Soon I. abandoned this obedience and went “on the same island into solitude, and lived a certain (small) summer in the vigil and prayers” (Life and Testament. 1896. T. 2. P. 4). OK. 1663 Nikon (by this time having left the Patriarchal See, but retaining control of a number of monasteries) transferred I. as a builder to the New Jerusalem in honor of the Resurrection of Christ husband. mon-ry, where will be. the patriarch supervised the construction of the Resurrection Cathedral. Apparently, due to a conflict with Nikon, I. left the monastery and, having received an invitation from F. M. Rtishchev, became a builder at the Moscow St. Andrew's Monastery in Plennitsy. Soon the husband took up the position of cellarer at the Novospassky Moscow Church in honor of the Transfiguration of the Lord. mon-ry. Despite the fact that the new cellarer did a lot to restore order in the economy of this privileged monastery, I. had clashes with the abbot of the monastery, Archimandrite. Prokhor, who disliked I., and with the brethren (the Life tells that once the monks rebelled against the cellarer because of poor quality fish). M. A. Rtishchev, who lived in the Novospassky Monastery and was close to the Tsar, came to I.’s defense.

At the Council in August. 1664 Russian the hierarchs recommended I. to the place of Archimandrite of the Chudov Monastery, which was vacant after the former. The abbot of the monastery, Pavel, was appointed Metropolitan of Sarsk and Podonsk (Krutitsa). Aug 19 in the Don Icon of the Mother of God in the Moscow monastery I. was ordained by the Novgorod Metropolitan. Pitirim to priest (previously Metropolitan Pitirim appointed I. “to priests, chanters, subdeacons and deacons”). Aug 22 Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich invited I. to become the archimandrite of the Chudov Monastery. According to the Old Believer Deacon. Fyodor Ivanov, the Tsar previously instructed M.A. Rtishchev to test I., “which faith he holds - old or new,” to which I. allegedly replied: “Ah, sir, I don’t know either the old faith or the new, but whatever the bosses say, I’m ready to do and listen to them in everything” (MDIR. 1881. Vol. 6. P. 229).

As the abbot of the Chudov Monastery, I. entered the inner circle of Alexei Mikhailovich and became one of the main executors of the tsar’s plans in organizing church affairs: in resolving the “Nikon case” and in the fight against the growing strength of the Old Believers. According to the Life of I., “the most illustrious great sovereign, Tsar and Grand Duke Alexei Mikhailovich, autocrat of all Great, Little, and White Russia, loved and revered this Archimandrite Joachim, and often commanded him to see his bright sovereign eyes, and conversed with He was very kind to him, and listened to him in sweetness about all his royal great [deeds], knowing his husband was righteous and virtuous, quiet and meek” (Life and Testament. 1896. Vol. 2. P. 12). 18-19 Dec. 1664 I. accompanied Metropolitan Krutitsky. Paul, who was sent to the New Jerusalem Monastery after Nikon, who took the staff of St. from Moscow. Petra. I. contributed to the return of the shrine to the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin. Chudovsky Archimandrite was part of the delegation that arrived on January 13. 1665 to Nikon in the New Jerusalem Monastery in order to receive from him letters from his patron, boyar N.A. Zyuzin, and to persuade Nikon to retire. The trip was successful: Nikon gave the letters, agreed to retire and not interfere with the election of a new primate (later the former patriarch changed his position).

I. defended the property interests of the clergy, while he sought to weaken the connection between parish priests and secular patrons of churches and to establish control of bishops over church property. In 1675 and 1687 The patriarch issued decrees establishing the same taxes for all dioceses in favor of episcopal sees. In 1676, a royal decree was issued prohibiting the disassociation of land to parish churches. I. managed to insist on its cancellation. The Patriarch achieved the decision of the Boyar Duma on August 25. 1680 on the provision of newly built buildings in the Moscow district. churches “from landowners’ and patrimonial lands” according to certain standards. These orders were extended to the entire territory of the state by scribal orders of 1681 and 1684. These lands were assigned to the Church in eternal possession and were recorded in the Patriarchal region in the books of the Treasury Order. The secular patron of the temple could no longer dispose of the land and the income from it at his own discretion. At the same time, control over these possessions was established by the bishops. All land used by church institutions began to be considered as church property. In 1685, during the new land survey, the patriarch tried to protect the inviolability of church estates from the arbitrariness of the scribes. The Patriarch's policy was continued in the actions of such bishops as Alexander Ustyuzhsky, Pskov Archbishop. Markell, Afanasy Kholmogorsky, who sought to free church lands from the patronage of parish communities in the North of Russia. Obviously, we are talking about a system of measures that was purposefully implemented by the episcopate headed by the first hierarch.

I. made a lot of efforts to maintain the authority of the patriarchal government and fought with personal opponents. One of the main dangers in this regard for I. was represented by the exiled Nikon, who did not recognize the legality of the trial against him, did not consider I. a patriarch, and called himself patriarch in letters and petitions. In the spring of 1676, shortly after the death of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, the Boyar Duma and I. decided to transfer Nikon from Ferapontov Belozersky in honor of the Nativity of the Most Rev. Mother of God husband monastery in Kirillov Belozersky in honor of the Dormition of the Most Holy. Mother of God husband monastery with a more strict regime of detention. Despite I.'s hostility to the deposed first hierarch, I. cannot be considered the initiator of this decision, the authors of which were primarily boyars who were sharply opposed to Nikon (in the first months after the death of Alexei Mikhailovich, Old Believer sentiments were strong at court). At a meeting of the Duma, the patriarch even spoke out against the boyars’ proposal to imprison Nikon in an earthen prison in the Cyril Monastery (that is, to deal with him in the same way as Alexey Mikhailovich did with Avvakum Petrov, Lazarus, Epiphanius and Fyodor Ivanov). On May 14, the decision of the Duma was approved by the Council. In 1678, the sympathies of Feodor Alekseevich and his entourage towards Nikon became obvious. According to biographer Nikon I. Shusherin, the autocrat repeatedly turned to I. with a request to release the deposed patriarch from captivity and allow him to live in the Resurrection Monastery (apparently, in connection with these plans there is a project by Simeon of Polotsk to transform the diocesan division of the Russian Church and about Nikon’s assimilation of the rank of pope), to which I. responded with a decisive refusal. Without the consent of the high priest, the king ordered Nikon to be transported to the Resurrection Monastery; Apparently, it was assumed that the former. the patriarch will also arrive in Moscow, where the tsar will meet him. However, Nikon died on the way. I. refused to bless the funeral according to the rite of burial of the patriarch and did not participate in the ceremony that took place on August 25. 1681 in the presence of the royal family. Perhaps as a result of this conflict, relations between the tsar and I. worsened, which resulted in a clash, the reason for which was the tsar’s decision to elevate his favorite, the Archbishop of Suzdal, to the rank of metropolitan on March 25, 1682. St. Hilarion. The tsar's actions aroused the anger of I., who took off the signs of his bishop's rank and put on a simple monastic dress, threatening to leave the Patriarchal throne. Soon the conflict was settled, and no later than April 16. the same year Hilarion received the rank of metropolitan. Oct.-Nov. 1675 I. brought the Kolomna archbishop to the episcopal court. Joseph, who allowed himself to attack the first hierarch. On the initiative of I. On March 14, 1676, the Council condemned and sentenced the husband to exile in Kozheezersky in honor of the Epiphany. monastery of the confessor of the deceased Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, Archpriest A. S. Postnikov. In April 1685 The Council condemned Metropolitan of Smolensk. Simeon (Milyukov). According to P.N. Popov, the main reason for the condemnation was the disagreement of Metropolitan. Simeon with I. on issues of church life (in October 1686, after repentance, Metropolitan Simeon returned to the pulpit). At the same time, I. was not a supporter of extreme measures of punishment for opponents; Apparently, he was not involved in the order to burn Pustozersky prisoners on April 14. 1682

From the end 60s XVII century in Moscow there were disputes about the time of the transposition of the Holy Gifts (see in Art. Eucharist), the initiator of which was the former. educator of the children of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich Simeon of Polotsk, who defended Catholicism. t.zr. in this matter. I. in this polemic supported the Grecophiles (Epiphanius (Slavinetsky), Euthymius Chudovsky, the Likhud brothers). I. could not effectively resist Simeon, who enjoyed the full trust of Tsar Feodor Alekseevich and Princess Sophia and created in 1679 (possibly in 1677) in the royal chambers (“in the Upper”) a printing house independent of the patriarchal censorship (it was closed at the insistence of I. in February 1683, after the death of Simeon). After 1680, Simeon's views were disseminated by his student Sylvester (Medvedev), whose condemnation in 1688-1689. the patriarch sought. The controversy was put to an end by the investigation carried out in the fall of 1689 into the conspiracy of F. Shaklovity, in which Sylvester was recognized as a participant, executed on February 11. 1691 (among other things, he was accused of hoping, through Sofia Alekseevna, to occupy the Patriarchal throne by deposing I.). In order to authoritatively end the theological polemic, the patriarch turned to other hierarchs. The Jerusalem Patriarch Dositheos II Notara sent in response the writings of Archbishop. Simeon of Thessaloniki, “Orthodox Confession” of St. Peter (Tombs) and other works, the Moldavian Metropolitan also sent books. Dositheus; they were translated by the Miracle monk Euthymius and testified by I. Convened by I. in January. 1690 The Council condemned Sylvester (Medvedev) and banned the distribution of Orthodox books. authors (mostly Ukrainian) containing “Latin heresies.” The works of Simeon of Polotsk, Peter (Mogila), Innocent (Gisel), Ioannikiy (Galjatovsky), Lazarus (Baranovich), Sylvester (Kosov) and others were banned. The 1st volume of the “Book of Lives of Saints” by St. Dimitri (Savich (Tuptalo)); the patriarch demanded the removal and alteration of the sheets, which, in his opinion, contained judgments that did not agree with the teachings of the Orthodox Church. Churches. By order of I., works were compiled, in which Orthodox. the position regarding the question of the time of the transfusion of the Holy Gifts found the most complete expression - “Austen” (author Evfimy Chudovsky) and “Shield of Faith” (author Archbishop Athanasius (Lyubimov), the name of the work was given by I.). Sat. “Austen” was attributed to I. for a long time. In fact, the patriarch owns the letters included in the collection to the Metropolitan of Kyiv. Gideon (Svyatopolk-Chetvertinsky) and Chernigov Archbishop. Lazar (Baranovich) and the teaching delivered at the Council of 1690.

I. was a strong opponent of foreign influence on Russian society. Undoubtedly, with the blessing of the patriarch, in the rank of installation of Jonah (Tugarinov?) Bishop of Vyatka and Great Perm (Aug. 23, 1674), an obligation was included not to enter into communication “with the Latins, and with the Luthors, and with the Calvins, and with other heretics” (cited . according to: Sedov. 2006. P. 137). In 1681, I. instructed Sylvester (Medvedev) to publicly denounce the views of the Calvinist preacher Ya. Belobotsky, who came to Moscow. OK. In 1682, by a district charter, the patriarch prohibited the purchase and sale of icons written on paper, especially “German, heretical” ones (AAE. 1836. Vol. 4. No. 200. pp. 254-256). With the active participation of I., a campaign was launched against the decision of the government of Sofia Alekseevna to grant Protestants and Catholics the right to build stone churches. Undoubtedly, by order of Patriarch Ignatius (Rimsky-Korsakov), archimandrite. Novospassky Moscow Monastery in honor of the Transfiguration of the Lord, wrote “The Word in Latin and Luther” with criticism of the “first adviser” (Prince V.V. Golitsyn), who “purchased for the sake of temporary and gifts” went to meet the “non-believers” (in the work “ First Councilor" is compared with King Solomon, who arranged "temples" for foreign wives, the author threatened Prince Golitsyn with the fate that befell the mayor Dobrynya, who, flattered by the gifts, allowed the construction of a lat. temple in Novgorod). There is a known episode when, in response to the request of Polish ambassadors of clergy, supported by Tsar Feodor Alekseevich, to attend the patriarchal service, I. responded with a sharp refusal: “But heretics are not allowed to be in the sanctuary” (quoted from: Life and Testament. 1879. P. 38) . The Patriarch insisted that at a gala dinner with the Tsar on February 28. In 1690, on the occasion of the birth of Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, no foreigners were present. In 1689, with the participation of I., Protestants were convicted. preachers K. Kuhlman and K. Nordeman. In 1690, by decision of I., the Jesuits were expelled from Moscow. The Patriarch was a firm opponent of partes singing, which was spread at court by the Poles and Ukrainians and loved by Tsar Theodore. In his spiritual testament I. called upon the Russian. people to resist foreign influence, recalling that he always fought against it, in particular protested against the appointment to the Russian Federation. regiments commanded by “heretical infidels.” In his will, I. calls on the Russian rulers “to not allow the heterodox-heretics of Roman churches, German churches and Tatar mosques in their kingdom and possession to build anywhere, and not to introduce new Latin foreign customs and foreign customs in dress” (Life and Testament . 1896. T. 2. pp. 44-45).

To establish Greek-oriented education in Russia. tradition, with the active support of I. in 1681, a school of “Greek reading, language and writing” (Typographical School) was established at the Printing Yard, headed by Timothy, the envoy of the Jerusalem Patriarch Dositheos. The school had 2 departments: Greek and Slavic; in 1686, 233 young men studied there. On major holidays, the patriarch received teachers and students who recited works in Greek. and Tserkovoslav. languages, after which the students and their mentors received gifts from the high priest. I. provided the school with books from the patriarchal library. In 1685, the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy, headed by the Likhud brothers, was opened in the Moscow monastery in honor of the Epiphany. Soon, with the support of the patriarch, a new building for the academy was built in the monastery. In 1687, the academy moved to the Zaikonospassky Moscow monastery in honor of the Image of the Savior Not Made by Hands, where in the 1st half. 80s XVII century unsuccessfully tried to arrange a Latin-Polish. school Sylvester (Medvedev). The following year, by order of the patriarch, students of the abolished Typographical School were transferred to the academy.

In the XVIII-XIX centuries. there were picturesque lists of portraits of I. in a series of images of other patriarchs, for example. in c. ap. St. Andrew the First-Called in the Miracle Monastery of the Moscow Kremlin (see: Inventory of icons, silver objects, fabrics and books of the Chudov Monastery, 1924 // GMMK ORPGF. F. 20. Op. 1924, D. 41). Dr. the sample (“in full bishop’s vestments, on the chest there are two panagias and a cross”) was in the collection of the Spaso-Iakovlevsky Monastery in Rostov (XVIII century (?), until 1966 it was kept in the State Historical and Cultural Museum of the Russian Federation; see: Kolbasova T.V. Portrait gallery of the Rostov Spaso-Yakovlevsky Monastery // SRM. 2002. Issue 12. P. 236, 253. Cat. The oval-shaped portrait came from the collection of A. N. Muravyov in the Central Museum of Art at the KDA (1st half of the 19th century, NKPIKZ; see: Catalog of preserved monuments of the Kiev Central Academy of Music, 1872-1922 / NKPIKZ. K., 2002 . P. 40. No. 68). In the 70s of the 19th century, I.’s image was part of a group of portraits placed in the congregational hall of the KDA (Rovinsky. Dictionary of engraved portraits. T. 4. Stb. 293).

In monumental painting, a half-length rectilinear image of I. in a medallion is found in the painting of the altar part of the Cathedral of the Presentation of the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God of the Sretensky Monastery in Moscow (1707; see: Russian historical portrait. 2004. P. 29; Lipatova S.N. Frescoes of the Cathedral of the Sretensky Monastery. M., 2009. P. 68). Like other patriarchs, he is written with a halo, wearing a sakkos, omophorion and miter, with 2 panagias and a cross, with a staff in his right hand. I. has large facial features, a forked beard streaked with sharp wedges, long strands of hair lying on his shoulders; the inscription is lost.

In accordance with the historical event, I. (in liturgical vestments, without individualizing the image) is depicted in the hagiographic iconography of St. Mitrofan of Voronezh in the hallmark “Consecration of St. Mitrofan as bishop", in particular on the icon of 1853, letters from I. I. Ivanov (Museum of the History of Obninsk), on the frame in gray. XIX century (Epiphany Cathedral in Elokhov in Moscow), on a frame of 1855 from c. Annunciation of the Virgin Mary in Yaroslavl (YAM; see: Kuznetsova O. B., Fedorchuk A. V. Icons of Yaroslavl 16-19 centuries: Cat. vyst. / YAHM. M., 2002. pp. 88-89. Cat. 43). I. is one of the main characters in the artist’s painting. V. G. Perov “Nikita Pustosvyat. Dispute about faith" (1880-1881, Tretyakov Gallery): on the left side of the composition is a gray-bearded old man in a robe and hood (doll), with the Gospel in his right hand.

Late images of the crowning of John and Peter Alekseevich are known (engraving from the early 80s of the 19th century based on a drawing by K. Brozhe), as well as prints with portraits of I. On the lithograph “All-Russian Patriarchs”, made according to a drawing by Sivkov in the workshop I. A. Golysheva in the village. Mstera (1859, Russian State Library), I. is presented in liturgical vestments, he has dark curly hair and a straight beard, slightly forked at the end, streaked with gray.

There are modern variants of portraits of I. In a series of works by V. V. Shilov with images of Russian. Patriarchs (after 1996, Patriarchal residence in Chisty Lane, in Moscow) I. is written in an academic manner, shoulder-length, in a patriarchal doll. For the 10th anniversary of the enthronement of His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II, a series of medals with images of 15 Russians were produced in a small edition. patriarchs (TSAM SPbDA, etc.).

Lit.: Rovinsky. Dictionary of engraved portraits. T. 2. Stb. 1005-1006; T. 4. Stb. 293; Savelov L.M. About painting a portrait of Patriarch Joachim // Old Years. St. Petersburg, 1912. Oct. pp. 55-56; Portrait in Russian art of the 17th century: Materials and research. M., 1955. S. 28-32; Ivanova E. Yu. “Portrait of Patriarch Joachim” by Karp Zolotarev, 1678 (from the collection of TGIAMZ): Results of restoration and research, 1992-1997. // Examination and attribution of works of art. art: IV scientific. Conf., 24-26 Nov. 1998, Moscow: Materials. M., 2000. P. 71-80; Moscow High Hierarchs. M., 2001. P. 70; Rus. ist. portrait: Age of Parsuna: Cat. vyst. / GIM. M., 2004; Gribov Yu. A. Litsevoy Title book. XVII century from collection State Historical Museum // Rus. ist. portrait: The Parsun era: Materials of the conference. M., 2006. pp. 113-141. (Tr. GIM; 155).

Y. E. Zelenina, M. E. Daen

And he remained there, forming the basis of the city garrison. On March 3 of the same year he was promoted to captain.

Thus, the future first hierarch quickly achieved the position of senior officer in the regiments of the “new order.” However, he was burdened by this service and communication with foreign colleagues who did not hide their disdain for the Russians. Therefore, having received news of the sudden death of all his household - his wife and four children, apparently from the plague, he decided to leave the world and become a monk in the Kiev Spaso-Preobrazhensky Mezhigorsky Monastery, which was located near his military unit. The tonsure probably took place in the winter-spring of the year.

From monk to metropolitan

In the same year, due to the fatal illness of Patriarch Pitirim, Metropolitan Joachim was summoned to Moscow and involved in the affairs of patriarchal administration.

Patriarchate

The question of legitimacy and relations with Patriarch Nikon

In response, Joachim pursued Nikon with persistence. After the death of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, Patriarch Joachim raised a whole case against Nikon and in the year transferred him to the Kirillov Monastery without trial under the strictest supervision. Later, despite repeated petitions from Tsar Theodore Alekseevich, Patriarch Joachim stubbornly did not agree to transfer Nikon to his beloved Resurrection Monastery and gave in at a time when Nikon was dying. Joachim did not agree to bury Nikon as a patriarch and was not present at his burial in the year, although the entire royal family appeared at them. In his place, the patriarch blessed Metropolitan Cornelius of Novgorod to perform funeral services as the sovereign wishes. The Patriarch also refused the precious miter of the deceased, which Tsar Theodore had sent him, and instead of the patriarch, the miter went to Saint Simeon of Smolensk, whom the Patriarch, shortly after the death of Tsar Theodore, deprived of his white hood and exiled to repentance in the Trinity-Sergius Monastery.

The fight against heterodox influence

The main efforts of Patriarch Joachim were aimed at fighting against heterodox, especially Roman Catholic, influence on Russian society, which at that time came mainly through Poland - either directly through Polish Jesuits, or through immigrants from Southern Russia, of whom there were especially many in the capital after the reunification of Ukraine with Russia in the year. In Moscow at that time, two religious and political parties were formed - one Latinizing, headed by the learned monk Sylvester (Medvedev), the other - zealots of Orthodoxy, headed by the Patriarch. Their confrontation was revealed in unrest over the question of the time of the transubstantiation of the Holy Gifts in the sacrament of the Eucharist. The Latin party, which was joined by Princess Sophia and her court, Prince V.V. Golitsyn and especially F.L. Shaklovity, many people from the clergy, including some hierarchs, raised this issue. Patriarch Joachim undertook a refutation of the teachings of the “pagemen”, turning to the Eastern Patriarchs for the paternal writings to which they referred. To combat the Polish-Latin trend, Patriarch Joachim asked the Eastern Patriarchs for two Greek scholars, monks of the Likhud brothers, sent by Patriarch Dositheos of Jerusalem. Patriarch Joachim put the Likhudov at the head of the “Greek” school (then the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy), founded at the Zaikonospassky monastery in the year, and instructed them to refute the works of the Latinists. Another assistant of the patriarch in polemics against Latinizers, as well as in all book matters in general, was the famous inquiry officer, monk Euthymius.

State affairs

Patriarch Joachim took a fairly prominent part in the political life of his time. The repeated change of reigning persons after the death of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich raised the importance of the patriarch, who acted as the highest person in the state, ensuring the stability of power.

He contributed to the destruction of localism under Tsar Theodore and energetically opposed the division of Russia into governorships projected around the same time with the establishment of hereditary governors from noble boyar families, " absolutely forbidden" do it.

Literature

- Barsukov, All-Russian Patriarch Joachim Savelov, St. Petersburg, 1890.

- Belokurov, S. A., "Sylvester Medvedev on the correction of liturgical books under Patriarchs Nikon and Joachim," Christian reading, 1885, part II.

- Belokurov, S. A., Christian Reading, 1886, № 7-8.

- Bogolyubsky, M. S., prot., Moscow hierarchy. Patriarchs, M., 1895, 31-45.

- Vorobiev, G., About the Moscow Cathedral 1681 - 1682, St. Petersburg, 1885.

- Gorsky, I., All-Russian Patriarch Joachim in the fight against schism, St. Petersburg, 1864.

- Edlinsky, M., priest, Ascetics and sufferers for the Orthodox faith. and the holy Russian land, St. Petersburg, 1903, 116-135.

- Mirkovic, G., About the time of the transubstantiation of St. Gifts, Vilna, 1886.

- Pisarev, N. N., Home life of Russian patriarchs, Kazan, 1904, 192-198.

- Sementovsky, N., Kyiv and its shrines(6th ed. supplemented and corrected), St. Petersburg. and Kyiv, 1881, 251.

- Skvortsov, G. A., Patriarch Adrian, his life and works.

- Smentsovsky, M. N., Likhud brothers, St. Petersburg, 1899.

- Smirnov, I., "Joachim, Patriarch of Moscow," Readings from the Society of Lovers of Spiritual Enlightenment, 1879, parts I-II; 1880, part I; 1881, part I (department of publishing house M., 1885).

- Soloviev, S. M., Russian history, book III, 468, 740-746, 775, 818-900, 905-928; 1046-1095; 1190.

- Tolstoy, M., Stories from I.R.Ts., 558-568, 574-591.

- Shlyapkin, St. Demetrius of Rostov and his time.

- Bulgakov, 1405, 1406.

- Gavrilov, Wanderer, 1873, №№ 1-3, №№ 6-9.

- Denisov, 95, 427, 501.

- Ratshin, 99.

- Stroev, P., 7, 37, 163.

- N.D., 12, 19.

- Arhang Institution. Ep. and her archpastors, Arkhangelsk, 1889, 3.

- Arr. to creativity St. father, v. 32 (Mansvetov, I., “How books took root among us,” etc.).

- Materials for the history of the schism, vol. IV.

- Life and Testament of Patr. Joachim, ed. separately Emperor. general lovers of ancient history. letters, 1880, No. 47.

- Reviewed. Ep. Reverend Jonathan, Bishop Yarosl. and Growth., Yaroslavl, 1881, 6.

- Chronicle of E. A., 576, 677, 671, 672.

- M. Nkr., vol. I, 508.

- Collection loves. spirit. read, M., 1888, 311.

- Right social security, 1866, January, 38 and p/s; 1867, November, 193.

- Histor. information about the city of Arzamas, 1911, 42.

- Soulful. read, 1897, part 2, 531.

- Rus. fallen, 1889, № 34, 401, 402; № 35, 415-418.

- Wanderer, 1872, February, 89.

- Histor. Vestn., 1880, January, 21; 1881, March, 548-549; November, 665-668; 1885, October, 115; 1886, t. 25, 589; 1890, October, 190; 1895, April, 544; 1896, July, 82 p/s.

- Right social security, 1873, July, 336.

- Rus. archive, 1889, book. 2nd, 304 (Kazan Metropolitan Markell); 1893, book. 3rd, 15-17 (N. Skvortsov, priest, Moscow Kremlin); 1895, book. 1st, No. 4, 530-531; 1910, book. 1st, No. 3, 423, 425-427; book 3rd, No. 9, 8.

- ZhMP, 1944, № 9, 15; 1945, № 3, 68; № 4, 66; № 7, 50; 1948, № 3, 6.

- BEL, vol. VI, 729-735.

- BES, vol. I, 1078-1079.

- RBS, vol. VIII, 174-177.

- PBE, vol. 6, stb. 729-735.

- Manuil (Lemeshevsky), Metropolitan, Russian Orthodox hierarchs of the period from 992 to 1892 (inclusive): parts 1-5, Kuibyshev, 1971 (typescript), part 2. Ancient Rus'. Questions of medieval studies, 2009, No. 4, 33-35.

The version expressed in Belokurov, S. A., Christian Reading, 1886, № 7-8.

Patriarch Joasaph II (1687-1672)

Tired of the hard struggle with the Patr. Nikon, the tsar and the bishops, in place of Nikon, who had been deposed by the council of 1667, immediately elected and appointed a person who did not arouse any controversy due to his extreme old age and inconspicuousness. It was Archimandrite Joasaph II of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery. He did not threaten to interfere in state affairs. He simply participated in the routine order of affairs. There was a big council in 1667. Business meetings of the cathedral after the condemnation of the patriarch. Nikon lasted from January until late summer. The honorary chairmanship belonged either to the eastern patriarchs or to their own, Joasaph II. The resolutions of the council of 1667 were, like the Stoglavy Council, a revision of all aspects of the life of the church. Extraordinary in the eyes of the Russians, thanks to the participation of other patriarchs, the formal authority of this council contributed to the final and confident resolution of the troubling ritual issues adopted under Nikon. All of them were resolved in complete fundamental agreement with the way Nikon himself began to solve them. Not only new rituals, so to speak, “Nikon’s” ones, were introduced as mandatory, but the formal justification of the Old Believer opposition was also undermined. In a harsh form, with the coloring of a Greek misunderstanding of Russian ritual psychology, the entire Council of the Hundred Heads was condemned, the fathers of which allegedly wrote their decrees “in simplicity and ignorance,” although the historical and liturgical ignorance of the Easterners themselves was in no way superior to the scientific ignorance of the Russian bishops together with the Old Believers. Not only have traditional Russian rituals been abolished, such as a special hallelujah, two fingers, 15 prostrations at the prayer of Ephraim the Syrian, etc., but the very authority of the entire Stoglavy Council has also been abolished. Many rules were published on behalf of the Council of 1667 to streamline the life of monasteries, clergy and laity. Naturally, many new rules regarding the order of worship were given. Fundamental wishes for reform were also expressed: a) to make the practice of large episcopal councils more frequent and b) following the example of the Greek Church, to generally increase the number of episcopal sees in the Russian Church, a task that found neither sympathy nor response from the Russian episcopate.

Patr. Joasaph II tried to implement in practice the cathedral decrees, which went against the text of the usual Moscow old printed books and with all the ritual habits and inertia of cult life, right down to the familiar technique of even Moscow bread rolls (not to mention the wide expanse of the Russian province) - printing prosphora with the old eight-pointed cross .

For getting rid of the nightmare of the Patr. Nikon Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, in his own way, did not pay cheaply to the obedient Russian episcopate. In gratitude for the peace achieved in the church and state, he almost completely abolished the validity of the Monastic Order of 1649, and returned to the Russian bishops their judicial privileges in almost the entire breadth and integrity. The liquidation of the Monastic Order itself dragged on, however, until 1677.

Patriarch Pitirim (1672-1673)

Pitirim was taken from the Novgorod Metropolis. Under Nikon, he was Krutitsky and deputy patriarchal seat from the moment Nikon left. As is known, Nikon, yearning for his return, found fault with all the actions of Pitirim, in particular, with the fact that Pitirim, at the royal and general desire, as the first hierarch, performed the ritual of procession on a donkey on Palm Sunday. All these were inconsistent claims of Nikon, who cowardly suffered from his capricious departure from the patriarchal throne. With such nagging, Nikon only created for himself one of the enemies who hated him at the time of the trial. Pitirim, who was promoted to the Novgorod metropolitanate after Nikon’s condemnation, was taken to the patriarchal position for his “anti-Nikonianism” in 1673, after the death of Joasaph II. After his 10-month, unremarkable patriarchate, Pitirim died. In his place, Joachim, once venerable and promoted by Nikon, was put in his place, again on the basis of being a reliable opponent of Nikon, who was languishing in exile.

Patriarch Joachim (1674-1690)

Joachim began his biography as a typical representative of the large class of Moscow service nobles. His family bore the surname Savelov. He served in the Chernigov-Kursk border zone with Poland. He had no theological school or even amateur church reading. According to the unfriendly characterization of the leader of the schism, Deacon Theodore, Joachim in his youth was far from churchly and was allegedly even illiterate. From a young age he lived in the village for a long time, hunted and rarely went to church. But by the age of 35, already in the service, he was widowed and decided to change his career. Having entered the church road, Joachim took monastic vows there in the south in Kyiv, in the Mezhigorsky monastery. With Patr. Nikon, he wanted to settle in his native Moscow region. In 1657 Patr. Nikon took him to his Iveron Monastery. From the moment Nikon left Moscow, the practical Joachim immediately took a position in the camp of Nikon’s opponents. From the Iversky Monastery in 1663 he was transferred to Moscow, to the Chudov Monastery, already with the rank of archimandrite. In 1672, Joachim was installed as Metropolitan of Novgorod to replace Pitirim, who became patriarch for one year (1672-1673). In view of Pitirim's illness, Joachim was summoned from Novgorod and involved in the affairs of the patriarchal administration, and after the death of Pitirim he was recognized as suitable to occupy the patriarchal position.

Having no school preparation for writing, Joachim in Moscow, approaching the administrative apparatus, relied in business techniques on a Kievite, monk Euthymius, who had been taken into the patriarchal office. He was the most strict orthodox among the recently arrived Kievites, who did not deny the Latin infection among his fellow countrymen. Of the boyars of that time, Joachim was on the side of the enthusiast of creating a school, pleasing to the tsar, Fyodor Mikhailovich Rtishchev, although the latter was alien to the superstitious fear of Muscovites of the Latin infection through the school.

As a conservative and positivist, Joachim directed his energy towards the implementation of the bishop's program, which was approved by the Great Council of 1667. It ran counter to the aspirations of the boyar and service class, and therefore persistent efforts were needed to implement it. Joachim was capable of this. He began to carry out this essentially Nikonian program from the moment he found himself at the Novgorod department. Already in Novgorod, Joachim issued a decree that church tribute from the clergy should be collected by the priestly elders themselves, and not by secular diocesan officials. Having become a patriarch, Joachim took systematic measures to actually implement the decisions of the Great Council so that the Monastic Order, hated by Nikon and the entire episcopate, would be abolished. For all the planned reforms in the spirit of preserving the previous privileges in administration, court and finance, Joachim immediately, in 1675, convened a council, at which he decided that the Monastic Order should be closed not in words and promises, but in deeds. And so that the administration, court and finances all pass into the hands of the clergy. And so that all secular officials, even if they belong to the ranks of the servants of the bishop's houses, and are placed on church lands, are not, nevertheless, in the order of official and administrative powers, independent bosses, but will always be only subordinate executors of the instructions and orders of the economic authorities, those in the monastic ranks. Secular officials were assigned auxiliary and executive services for the audit and inventory of the property of churches and monasteries, for conducting judicial investigations and for police functions.

From the very moment he assumed the patriarchate, Joachim, as a lover of order and legality, immediately in 1675 convened a council and at it raised the question of the still unfulfilled decision of the Council of 1667 on the abolition of the Monastic Order and the acceleration of the implementation of the complete non-jurisdiction of the clergy to secular authorities. Due to inertia, the liquidation period for the Monastic Order was still dragging on. Patr. Joachim achieved a resolution from the council to permanently close it, which happened in 1677. If you look back, Patr. Joachim clearly carried out Nikon’s program: he fought against the dominance of the tsarist administration. And so it was. The bishops overthrew Nikon, but stood for his program, sought the same thing that the overthrown Nikon sought, but now in the confidence that the tsarist government would no longer be fundamentally concerned about this struggle. All the patriarchs, ending with the last Adrian, defended the fundamentally historically outdated, “appanage” principle of the inviolability of immovable church property. They continued to fuss about possible ways, direct and roundabout, of their further expansion. And in particular, of course, they tried to maximally cleanse the entire economic department of the church from any participation in it by royal officials. The same elimination of government officials was pursued in the administration of the parish clergy. The same fundamental independence from the secular element was pursued in the court procedure, not only in cases of a spiritual nature, but, if possible, in all cases of a civil and criminal nature, both over the clergy and over all people of church land. Patriarch Joachim at the council of 1675 carried out a number of measures to undermine the role and importance of secular officials in diocesan administration. From now on, it is prescribed that judges who are only in the clergy or monastic rank, but in no way lay officials, even if they belong to the bishop’s department, are in charge of spiritual matters and matters concerning clergy. All former lay officials are given only the role of clerks and executors of spiritual decisions and sentences.

The issue of the growth of church land ownership, despite the resistance of the statist program to it, could not be resolved in an indiscriminately negative manner. This would be an unnatural struggle against the growth of the entire national life. There was a settlement of people across new lands, a natural proliferation of the population and, along with all this, a proliferation of parish churches and partly monasteries. There was also a law since the moment of liquidation of the turmoil under Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich on the provision of new churches with land plots that would provide them with a minimum amount of land. Such plots, registered in general scribe books, were called “scribal lands.” These church allotments were sabotaged by the secular authorities, and, according to the boyar verdict of 1676, they ceased altogether. Patr. Joachim raised a sharp struggle against this lawlessness and achieved its abolition. A new land survey was planned for 1680. And here is Patr. Joachim had already passed a law so that in the future there would be no landless churches, but that the scribal lands would be demarcated for all churches.

But the tsarist government was uncompromising on the issue of the tax burden on all church and monastic lands according to the principles of the Code of 1649. Increased taxes on church estates, compared with fees on other service classes, were left in full force. The impending pressure from Peter the Great intensified from the very beginning of the Code. Already now the government was sending its disabled people, that is, the wounded and simply old service people, to monasteries and bishops' houses to feed them. The government itself, which had already begun to create philanthropic institutions, proposed in 1678 to expand the patriarchal almshouses in Moscow to accommodate at least 412 people. The Council of 1683, on a proposal made by the tsarist government, decided to sort out the poor and sick people by city and place them in church almshouses and hospitals.

The page was generated in 0.08 seconds!

Patriarch of Moscow (1674-1690).

Patriarch Joachim (in the world Ivan Petrovich Savelov) was born on January 6 (16), 1621 in. He came from a family of Mozhaisk nobles, the Savelovs, known since the end of the 15th century.

In his youth, the future high priest was in military service on the southern borders of the Russian state. Having become an Ovodov in 1655, he left military service and took monastic vows at the Mezhigorsky Monastery in Kyiv (now in Ukraine).

In September 1657, Joachim became a monk and then the “builder” of the Valdai Iveron Monastery. In 1661, the patriarch transferred him to the position of “builder” at the Resurrection New Jerusalem Monastery.

Soon Joachim was transferred to Moscow, where he labored first in the St. Andrew's Monastery, and then in Novospassky. In 1664, he was appointed archimandrite of the Moscow Chudov Monastery, thanks to which he became close to the royal court and personally to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich.

In 1672, Joachim was appointed Metropolitan of Novgorod. Soon, due to the illness of Patriarch Pitirim, Metropolitan Joachim was summoned and involved in the affairs of patriarchal administration.

Patriarch Joachim was distinguished by his zeal for the strict implementation of church canons. He revised the rites of the liturgy and eliminated some inconsistencies in liturgical practice. In the fight against the schism, the high priest resorted not only to administrative measures, but also to exhortations. In the internal church administration under him, it was established that spiritual affairs everywhere should be conducted only by clergy. During the period of Patriarch Joachim's primacy, the Nizhny Novgorod, Ustyug, Kholmogory, Tambov and Voronezh dioceses were established. The Patriarch also contributed to the subordination of the Moscow Patriarchate to the Kyiv Metropolis.

With the blessing of Patriarch Joachim, in 1685, the brothers Ioannikiy and Sophrony Likhud founded a theological school at the Zaikonospassky Monastery. This school marked the beginning of the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy.

In the field of public administration, Patriarch Joachim also proved himself to be an energetic and consistent politician. During the years of his reign, the primate exercised significant influence on state affairs. After the death of the Tsar in 1682, in the context of the turmoil that arose regarding the issue of succession to the throne, the Patriarch actively supported the party of the Naryshkins and the Tsarevich, acted as a mediator between the warring parties and took measures to stop the Streltsy uprising.

The Patriarch resolutely opposed the plans for the coronation of the princess, which gave rise to a plan among her supporters for the deposition and even murder of Joachim. During the events of August 1689, the high priest actually took sides