Studies of the speech voice of F. Chaliapin

Great Performers of the 20th Century

Fyodor Chaliapin. Tsar Bass

Like Sabinin in Glinka's opera, I exclaim:

“Immeasurable joy!”

Great happiness fell from the sky on us!

A new, great talent has been born...

(V. Stasov)

We live in an amazing time when miracles have become common, everyday occurrences. Thanks to one of these miracles, we now, just like Vladimir Vasilyevich Stasov once did, can exclaim: “Immeasurable joy!”- we hear Chaliapin’s voice.

Tsar Bass

“Someone said about Chaliapin,- wrote V.I. Nemirovich-Danchenko, - when God created him, he was in a special good mood, creating for the joy of everyone.”

This voice, once heard, is truly impossible to forget. You return to it again and again, despite the imperfections of the old recordings. There were wonderful voices both before and after Chaliapin, but few can compare with his high, “velvety” bass, which was distinguished by incredible expressiveness. And the listener is fascinated not only by the unique timbre, but also by how accurately and subtly the singer was able to convey the slightest shades of feelings inherent in the work, be it an opera part, a folk song or a romance.

Chaliapin raised vocal art to new heights, teaching lessons of musical truth to those around him and generously sharing his secrets with future generations of artists.

And the life story of the Russian Tsar Bass is a lesson for everyone. No matter what conditions you live in, as long as you have a spark of talent, follow your dreams, work, strive for perfection... And everything will work out.

Since September 24, 1899, Chaliapin has been the leading soloist of the Bolshoi and at the same time the Mariinsky theaters, with triumphant success on tours abroad. In 1901, at La Scala in Milan, with great success, he sang the role of Mephistopheles in the opera of the same name by A. Boito with Enrico Caruso, conducted by A. Toscanini. The world fame of the Russian singer was confirmed by tours in Rome (1904), Monte Carlo (1905), Orange (France, 1905), Berlin (1907), New York (1908), Paris (1908), London (1913/14).

The divine beauty of Chaliapin's voice captivated listeners from all countries. His high bass, delivered naturally, with a velvety, soft timbre, sounded full-blooded, powerful and possessed a rich palette of vocal intonations. The effect of artistic transformation amazed the listeners - not only appearance, but also the deep inner content conveyed by the singer’s vocal speech. In creating capacious and scenically expressive images, the singer is helped by his extraordinary versatility: he is both a sculptor and an artist, writes poetry and prose. Such versatile talent of the great artist is reminiscent of the masters of the Renaissance - it is no coincidence that his contemporaries compared his opera heroes with the titans of Michelangelo.

Chaliapin's art crossed national boundaries and influenced the development of the world opera theater. Many Western conductors, artists and singers could repeat the words of the Italian conductor and composer D. Gavadzeni: “Chaliapin’s innovation in the field of dramatic truth of operatic art had a strong impact on the Italian theater... The dramatic art of the great Russian artist left a deep and lasting mark not only in the field of performance of Russian operas by Italian singers, but in general, on the entire style of their vocal and stage performances.” interpretations, including works by Verdi..."

Of particular importance was Chaliapin’s participation in the “Russian Seasons” as a promoter of Russian music, primarily the work of M. P. Mussorgsky and N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov. He was artistic director Mariinsky Theater (1918), elected member of the directors of the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theaters. Having gone abroad on tour in 1922, Chaliapin did not return to Soviet Union, lived and died in Paris (in 1984, Chaliapin’s ashes were transferred to the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow).

The greatest representative of Russian performing art, Chaliapin, was equally great both as a singer and as a dramatic actor. His voice - amazing in its flexibility and richness of timbre - sounded either with soulful tenderness, sincerity, or with striking sarcasm.

Masterfully mastering the art of phrasing, the finest nuances, and diction, the singer imbued each musical phrase with figurative meaning and filled it with deep psychological subtext. Chaliapin created a gallery of diverse images, revealing the complex inner world of his heroes.

The artist’s pinnacle creations were the images of Boris Godunov (“Boris Godunov” by M. P. Mussorgsky) and Mephistopheles (“Faust” by Charles Gounod and “Mephistopheles” by Arrigo Boito). Other roles include: Susanin (“Ivan Susanin” by M. I. Glinka), Melnik (“The Mermaid” by A. S. Dargomyzhsky), Ivan the Terrible (“The Woman of Pskov” by N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov), Don Basilio (“The Barber of Seville” "G. Rossini), Don Quixote ("Don Quixote" by J. Massenet).

Chaliapin was an outstanding chamber singer: a sensitive interpreter of the vocal works of M. I. Glinka, A. S. Dargomyzhsky, M. P. Mussorgsky, P. I. Tchaikovsky, A. G. Rubinstein, R. Schumann, F. Schubert, as well as a soulful performer of Russian folk songs. He also acted as a director (productions of the opera “Khovanshchina”, “Don Quixote”). He acted in films. He also owns sculptural and painting works.

The memory of the artist is immortalized in the city of his childhood - Kazan. On the occasion of the 125th anniversary of his birth, the world's first city monument to F.I. Chaliapin, made by sculptor Andrei Balashov, was unveiled here. He took a place on a pedestal near the Epiphany Cathedral, where Chaliapin was once baptized, on the main street of the city.

Arias from the opera "Boris Godunov" M. P. Mussorgsky

Chaliapin loved Mussorgsky most of all composers. And he sang it in such a way that it seems as if everything created by Mussorgsky was created specifically for Chaliapin. Meanwhile...

“My greatest disappointment in life is that I did not meet Mussorgsky. He died before I arrived in St. Petersburg. My grief..."

Yes, they never knew each other. However, no, this is not so. Mussorgsky really did not know Chaliapin. And this is very sad to think about. How happy Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky would have been if he had heard and seen Chaliapin perform his Tsar Boris, his Varlaam, Pimen, Dositheus, all his men whom he sang in music with such love, with such great pain and compassion.

And Chaliapin knew Mussorgsky. He understood and loved him like his closest friend. With the heart of a great artist, he felt every thought of his music, knew every note in it. All of Mussorgsky's works that the bass could sing were in his repertoire. The opera "Boris Godunov" has three bass parts. And all three were performed by Chaliapin.

We know that Chaliapin was not only a great singer, but also a great actor. And although we have never seen Chaliapin play, we understand this by looking at his portraits in roles. It’s hard to believe that this is the same person, that it’s all Chaliapin.

And it’s not just makeup and costume that change an artist.

Boris Godunov. Boris Godunov has a strong, strong-willed face; he is a handsome, courageous man with a sharp, inquisitive gaze. But somewhere in the depths of his smart, beautiful eyes, great anxiety, almost despair, is beating and screaming.

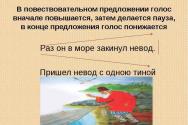

Listening: M. Mussorgsky. Boris' monologue (prologue) "The soul grieves..." from the opera “Boris Godunov”, performed by F. Chaliapin.

Chaliapin's daughter, Irina, recalls:

“The curtain rose, and to the ringing of bells, “led by the hands of the boyars,” Tsar Boris appeared.

The soul grieves...

We listen to Chaliapin sing. Beautiful, juicy, thick, I would like to say - regal voice. Only in this royal greatness there is no peace. The anxiety and sadness are clearly heard in the voice. Tsar Boris is in trouble in his soul. He is not pleased with the ringing of bells, nor is he pleased with the solemn election to the kingdom. But Boris Godunov is a man of strong will. He overcame his anxiety. And now, in Russian, broadly:

And then call the people to a feast...

It’s as if this mighty, generous bass hugged everyone:

All free entry; all guests are dear...

Listening: M. Mussorgsky. Boris' monologue “I have reached the highest power...”(Act 2) from the opera “Boris Godunov”, performed by F. Chaliapin.

Pimen - completely different. This old man knows a lot. Sees a lot. He is calm and wise, he is not tormented by remorse, which is why his gaze is so straight and calm. Remember, in Pushkin: "Night. Cell in the Chudov Monastery. Pimen writes in front of a lamp".

The voices of the strings in the orchestra sound muffled, note after note is strung slowly and monotonously. Like the quiet rustle of a quill pen on ancient parchment, as if the intricate script of Slavic writing stretches out, telling about the “past fate of the native land.”

One more, last legend and my chronicle is finished...

Wise tired voice. This man is very old. All the passion, all the tension that so shocked us in Boris disappeared from Chaliapin’s voice. Now it sounds very smooth, very calm. And at the same time, there is some elusive characteristic in it. It reminds me of something. But what? However, it may not remind you of anything: you have probably never heard church singing. Only in the movies. And Chaliapin knew well how priests sing: always at least a little, but “in the nose,” with a little nasal. Listen to the voice of Chaliapin Pimen... The singer gives it a barely noticeable “church” tint. He feels that Mussorgsky's music requires this.

Almost all of Pimen’s monologue sounds leisurely and thoughtful. But there is no monotonous, boring monotony in Chaliapin’s voice. If in the role of Boris he can be compared to an artist’s palette, on which you see a variety of colors - blue, yellow, green, and red, then the voice of Chaliapin-Pimen is like a palette with different shades of the same paint (for some reason I sometimes it seems lilac) from thick dark to light; blurry.

Listening: M. Mussorgsky. Monologue of Pimen (1 act) from the opera “Boris Godunov”, in Spanish. F. Chaliapin.

Varlaam. Here he is, in full view - a sloppy, flabby, half-drunk tramp. But as soon as you look into his eyes, you immediately see: no, this fugitive monk is not at all so simple - his eyes are smart, cunning and very unkind.

How does Chaliapin himself imagine him?

“Mussorgsky, with incomparable art, conveyed the bottomless melancholy of this tramp... The melancholy in Varlaam is such that you could at least hang yourself, and if you don’t want to hang yourself, then you have to laugh, invent some kind of riotous drunkenness, as if it were funny...”

That's why Varlaam-Chaliapin has such eyes.

In Pushkin's tragedy, Varlaam's role is very small. He doesn't have big monologues. And Mussorgsky, when creating his Varlaam, did not invent any special arias for him. But remember, Pushkin said: “Varlaam sings the song “How it was in the city in Kazan”?

The all-knowing Stasov found the original text of this ancient Russian song, which tells about how Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible took Kazan. This song became the first characteristic of Varlaam. And instead of the second song of Varlaam, indicated by Pushkin, “The young monk took his hair,” Mussorgsky’s Varlaam sings the song “How He Rides.”

Two songs tell us about the character of Varlaam. And how they say it! Especially if Chaliapin sings Varlaam.

We listen to the first song - “As it was in the city in Kazan” and understand that Chaliapin, speaking about how he imagines his Varlaam, did not reveal to us everything that is in his fugitive monk.

As with gunpowder, that barrel began to spin,

She rolled through the tunnels, through the tunnels,

Yes, and she banged...

Oh no, it’s not just drunken revelry that can be heard in Varlaam’s voice. Stasov says that Varlaam “sings like an animal and fiercely.” He says this about Mussorgsky’s music, but Chaliapin also sings exactly like that – “bestially and fiercely.” Enormous strength - dense, irrepressible - is felt in this man. Someday she will break free!.. And she breaks out.

"Subsequently,- writes Stasov, - this same Varlaam with a mighty hand will raise a formidable popular storm against the Jesuits who wandered into Russia with False Dmitry". We are talking about a scene that was banned by censorship in pre-revolutionary times. This final scene opera - a popular uprising near Kromy, in which Varlaam plays a very important role.

Here's a runaway drunkard monk!

Three roles - three different people. Such different people, of course, and the voices should be completely different. But since we are talking about Chaliapin, it is quite clear that everyone will have the same voice - the unforgettable Chaliapin bass. You will always recognize it if you have heard it at least once.

Listening: M. Mussorgsky. Song of Varlaam (1 act) from the opera “Boris Godunov”, performed by F. Chaliapin.

Farlafa's Rondo from M. I. Glinka's opera "Ruslan and Lyudmila"

F. I. Chaliapin performed the roles of Ruslan and Farlaf in M. I. Glinka’s opera “Ruslan and Lyudmila”, and it was in the second role that, according to A. Gozenpud, he reached the top, surpassing his famous predecessors.

Insolence, boasting, unbridled impudence, intoxication with one’s own “courage,” envy and malice, cowardice, lust, all the baseness of Farlaf’s nature were revealed by Chaliapin in the performance of the rondo without caricatured exaggeration, without emphasizing or pressure. Here the singer reached the pinnacle of vocal performance, overcoming technical difficulties with masterly ease.

Listening: M. Glinka. Rondo Farlafa from the opera “Ruslan and Lyudmila”, performed by F. Chaliapin.

Song of the Varangian guest from N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera “Sadko”

The song of the Varangian guest performed by Chaliapin is stern, warlike and courageous: “On the formidable rocks the waves are crushed with a roar.” The timbre of a low male voice and the thick sonority of wind instruments, mainly brass instruments, harmonize well with the entire appearance of the Varangian - a brave warrior and sailor.

The part of the Varangian Guest is fraught with enormous artistic possibilities, allowing you to create a vivid stage image.

Listening: N. Rimsky-Korsakov. Song of the Varangian guest from the opera “Sadko”, performed by F. Chaliapin.

Aria of Ivan Susanin "You will rise my dawn..." from the opera “Ivan Susanin” by M. I. Glinka

“Shalyapinsky Susanin is a reflection of an entire era, this is a virtuoso and mysterious embodiment folk wisdom, the wisdom that saved Rus' from destruction in difficult years of trials.”

(Edward Stark)

Chaliapin brilliantly performed Susanin's aria at a private debut at the Mariinsky Theater when he came from the provinces to conquer the capital and was accepted onto the imperial stage on the day of his full majority, February 1 (13), 1894.

This audition took place on the recommendation of the patron of the arts, a major official T. I. Filippov, known for his friendship with Russian composers and writers. In Filippov's house, young Chaliapin met with M.I. Glinka's sister Lyudmila Ivanovna Shestakova, who showered young singer praises after hearing him perform the aria of the Russian national hero.

Ivan Susanin played a fateful role in the work of Fyodor Chaliapin. In the spring of 1896, the singer decides to go to Nizhny Novgorod. There he meets S.I. Mamontov - Savva the Magnificent, industrialist and philanthropist, opera theater reformer, creator of the Russian Private Opera and a true collector of talent. On May 14, the play “Life for the Tsar” with Chaliapin in the title role began regular performances of Mamontov’s troupe, which toured Nizhny Novgorod.

Listening: M. Glinka. Aria Susanina "You will rise my dawn" from the opera “Ivan Susanin”, in Spanish. F. Chaliapin.

Chaliapin was unusually musical. He not only understood and knew music, he lived in it, music permeated his entire being. Every sound, every breath, gesture, every step - everything was subordinate to her.

The great singer always “selected” from the richest arsenal of technical techniques exactly the one that the musical image demanded of him. Chaliapin gives his voice completely to the service of music. He fiercely hates singers who consider their own singing to be the main thing in their activity.

“After all, I know singers with beautiful voices, they control their voices brilliantly, that is, they can sing loudly and quietly at any moment... but almost all of them sing only notes, adding syllables or words to these notes... Such a singer sings beautiful... But if this charming singer needs to sing several songs in one evening, then one is almost never different from the other. Whatever he sings about, love or hate. I don’t know how the average listener reacts to this, but personally, after the second song, sitting at a concert becomes boring.”

Do not think, however, that a deep understanding of music came to Chaliapin by itself. He had mistakes, failures, and breakdowns. There was dissatisfaction with myself. This was the case even with Mussorgsky, whom he adored.

“I stubbornly did not betray Mussorgsky, I performed his works at all the concerts in which I performed. I sang his romances and songs according to all the rules of cantilena art - I gave costal breathing, kept my voice in a mask and generally behaved like a decent singer, but Mussorgsky came out dull for me...”

This is how it was when I was young. And Chaliapin tries, rehearses, achieves. Like Chaliapin, he passionately strives for knowledge, greedily absorbs everything that seems necessary to him to achieve a single goal. This goal is to serve music.

Presentation

Included:

1. Presentation - 15 slides, ppsx;

2. Sounds of music:

Glinka. Opera "Ivan Susanin":

Aria Susanina “You will rise my dawn...”, mp3;

Glinka. Opera "Ruslan and Lyudmila":

Rondo Farlafa, mp3;

Mussorgsky. Opera "Boris Godunov":

Boris' monologue (prologue), mp3;

Pimen's monologue (1 act), mp3;

Song of Varlaam (1 act), mp3;

Boris' monologue (act 2), mp3;

Rimsky-Korsakov. Opera "Sadko":

Song of the Varangian Guest, mp3;

(all works performed by Fyodor Chaliapin)

3. Accompanying article, docx.

On February 13, 1873, a man of rare talent, Fyodor Ivanovich Chaliapin, was born. The fame of his unique booming bass and powerful talent as a dramatic actor thundered throughout the world, but he was far from an unambiguous person.

Ashamed of his origins

The fate of Fyodor Chaliapin is the story of how a peasant boy managed to rise to the heights of not only Russian, but also world fame. He became the embodiment national character and the Russian soul, which is as broad as it is mysterious. He loved the Volga, said that the people here are completely different, “not squanderers.” Meanwhile, according to the memoirs of contemporaries, Chaliapin seemed to be embarrassed by the peasants. Often, while relaxing with friends in the village, he was unable to have a heart-to-heart talk with the peasants. It was as if he was putting on a mask: here he is, Chaliapin, a shirt-sleeve guy with a great soul, and at the same time a “master”, constantly complaining about someone and hinting at his bitter fate. There was that anguish in him that is so characteristic of Russian people.

The peasants idolized the “golden guy” and his songs, which “touch the soul.” “If only the king would listen,” they said. “Maybe I would cry if I knew peasant life.” Chaliapin liked to complain that people were getting drunk, noting that vodka was invented solely so that “the people would not understand their situation.” And that same evening I got drunk.

Ingratitude

It is unknown what Chaliapin’s fate would have been like if in 1896 he had not met the great Russian philanthropist Savva Mamontov, who persuaded him to leave the Mariinsky Theater and move to his opera house. It was while working for Mamontov that Chaliapin gained fame. He considered Mamontov’s four years the most important, because he had at his disposal a repertoire that allowed him to realize his potential. Chaliapin was well aware that as a connoisseur of everything beautiful, Mamontov could not help but admire him. Wanting to one day test Savva Ivanovich’s attitude towards himself, Fyodor Ivanovich stated that he wanted to receive a salary not monthly, but as a guest performer, for each performance. They say, if you love, pay. And when Chaliapin was reproached for ingratitude, because it was thanks to Mamontov that he received his name, fame, and money, the bass exclaimed: “Should I also be grateful to the masons who built the theater?” They said that when Mamontov went bankrupt, Chaliapin never visited him.

Heavy character

Chaliapin had a bad character. Not a day went by without him quarreling with someone. On one of these days, before performing the main role in Boris Godunov, Chaliapin managed to quarrel with the conductor, the hairdresser and... the choir. That evening he sang especially delightfully. Chaliapin himself said that he felt like Boris on stage. Friends aptly noted that after quarrels, Chaliapin always sang magnificently. He didn't try to choose words or smooth out rough edges. He often did not get along with conductors, believing that many of these “idiots” did not understand what they were playing: “Notes are not music! Notes are just signs. We still need to make music out of them!” Among Fyodor Ivanovich’s acquaintances there were many artists: Korovin, Serov, Vrubel, Levitan. Chaliapin could directly state that he did not understand what was in the picture: “Is this a person? I wouldn’t hang one like that!” As a result, he fell out with almost everyone.

Unwillingness to forgive

Chaliapin always repeated that he did not like to forgive: “Forgiving is the same as making a fool out of yourself.” He believed that if you let it, anyone will start to “exploit” you. There is a known incident that happened to him in Baku. He had a big quarrel with the manager, who after the performance threw out the unknown singer without a penny with the words: “Drive him to the neck!” Much later, the woman, while in the capital, decided to visit a friend whose name had already become popular. Having learned who was asking him, Chaliapin said loudly: “Entrepreneur? From Baku? Drive her in the neck!”

Left his homeland

He always believed that Russian people should live better. But the events of 1905 only worsened the situation. Looking out the window, Chaliapin said that “it is impossible to live in this country.” “There is no electricity, even the restaurants are closed...” And despite the complaints, he will live in Russia for another 17 years - his whole life. During this time, he made his film debut, playing the role of Ivan the Terrible, repeatedly acted as a director and became the director of the Mariinsky Theater, and also received the title People's Artist. Chaliapin would be prohibited from returning to the Land of Soviets and deprived of the title of People's Artist in 1927 due to his alleged reluctance to “return and serve the people whose title of artist was awarded to him.” Yes, Chaliapin had not been to his homeland for 5 years - in 1922 he went on tour abroad, and on the eve of the “verdict” he dared to give money from the concert to the children of emigrants (according to another version, Chaliapin generously financed the monarchists in exile). Be that as it may, Chaliapin will no longer be able to see his home.

Weighed down by fame

At the beginning of the 20th century, Fyodor Ivanovich Chaliapin was one of the most popular people not only in Russia, but throughout the world. Everyone loved him, regardless of rank and class: ministers and coachmen, composers and carpenters. They recalled that in the very first season of working for Mamontov, Chaliapin became so famous that any dinner in a large restaurant turned into a silent scene: Chaliapin ate and the public watched. Later, Chaliapin would complain that he was too tired of “all this nonsense”: “I can’t stand fame! It seems to them that it is very easy to sing. There is a voice, he sang and, up, Chaliapin!” Of course, there were those who did not understand Chaliapin. They said: “Good for him! Sing and welcome - here’s the money for you.” Apparently, those who slandered him forgot that talent alone will not get you far. To get to such heights, and even more so to stay, one had to work tirelessly. And Chaliapin, of course, was a great worker.

Chaliapin felt especially tired towards the end of his life. In the last months before his death from leukemia, Fyodor Ivanovich dreamed of singing for a couple more years, and then, as he said, “to retire, to the village.” “There I will be called Prozorov, after my mother. But Chaliapin is not needed! Was and floated!”

I wanted to express the intonation

In his memoirs “Mask and Soul,” Chaliapin wrote: “There are letters in the alphabet and signs in music. You can write everything with these letters and draw with these signs. But there is an intonation of a sigh. How to write or draw this intonation? There are no such letters and signs!” Throughout his life, Fyodor Ivanovich perfectly conveyed this most subtle intonation. It was he who opened Russian opera not only to the world public, but also to Russia itself. It was almost always difficult, but Chaliapin possessed those qualities of national character that allowed him to become a Russian asset and pride: amazing talent, breadth of soul and the ability to hide the secret somewhere deep inside.

Fyodor Ivanovich Chaliapin was born on February 13, 1873 in Kazan, into the poor family of Ivan Yakovlevich Chaliapin, a peasant from the village of Syrtsovo, Vyatka province. Mother, Evdokia (Avdotya) Mikhailovna (nee Prozorova), comes from the village of Dudinskaya in the same province. Already in childhood, Fyodor had a beautiful voice (treble) and often sang along with his mother, “adjusting his voices.” From the age of nine he sang in church choirs, tried to learn to play the violin, read a lot, but was forced to work as an apprentice to a shoemaker, turner, carpenter, bookbinder, copyist. At the age of twelve he participated in the performances of a troupe touring in Kazan as an extra. An insatiable craving for theater led him to various acting troupes, with whom he wandered around the cities of the Volga region, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, working either as a loader or as a hookman at the pier, often going hungry and spending the night on benches.

"... Apparently, even in the modest role of a chorister, I managed to show my natural musicality and good vocal abilities. When one day one of the baritones of the troupe suddenly, on the eve of the performance, for some reason refused the role of Stolnik in Moniuszko’s opera “Pebble”, and replaced him There was no one in the troupe, then the entrepreneur Semyonov-Samarsky asked me if I would agree to sing this part. Despite my extreme shyness, I agreed: it was too tempting: the first serious role in my life, I quickly learned the part and performed.

Despite the sad incident in this performance (I sat past a chair on stage), Semyonov-Samarsky was still moved by both my singing and my conscientious desire to portray something similar to the Polish tycoon. He added five rubles to my salary and also began assigning me other roles. I still think superstitiously: it’s a good sign for a newcomer to sit past the chair in the first performance on stage in front of an audience. Throughout my subsequent career, however, I kept a vigilant eye on the chair and was afraid not only of sitting past, but also of sitting in another’s chair...

In this first season of mine, I also sang Fernando in Troubadour and Neizvestny in Askold’s Grave. Success finally strengthened my decision to devote myself to the theater."

Then the young singer moved to Tiflis, where he took free singing lessons from the famous singer D. Usatov, and performed in amateur and student concerts. In 1894, he sang in performances held in the St. Petersburg country garden "Arcadia", then at the Panaevsky Theater. On April 5, 1895, he made his debut as Mephistopheles in the opera Faust by Charles Gounod at the Mariinsky Theater.

In 1896, Chaliapin was invited by S. Mamontov to the Moscow Private Opera, where he took a leading position and fully revealed his talent, creating over the years of work in this theater a whole gallery of unforgettable images in Russian operas: Ivan the Terrible in “The Woman of Pskov” by N. Rimsky -Korsakov (1896); Dosifey in “Khovanshchina” by M. Mussorgsky (1897); Boris Godunov in the opera of the same name by M. Mussorgsky (1898) and others. “One more great artist has become,” V. Stasov wrote about the twenty-five-year-old Chaliapin.

Communication at the Mamontov Theater with the best artists Russia (V. Polenov, V. and A. Vasnetsov, I. Levitan, V. Serov, M. Vrubel, K. Korovin and others) gave the singer powerful incentives for creativity: their scenery and costumes helped in creating a convincing stage image. The singer prepared a number of opera roles in the theater with the then novice conductor and composer Sergei Rachmaninov. Creative friendship united the two great artists until the end of their lives. Rachmaninov dedicated several romances to the singer, including “Fate” (poems by A. Apukhtin), “You Knew Him” (poems by F. Tyutchev).

The singer's deeply national art delighted his contemporaries. “In Russian art, Chaliapin is an era like Pushkin,” wrote M. Gorky. Based on the best traditions Chaliapin opened the national vocal school new era in the national musical theater. He managed to amazingly organically combine the two most important principles of operatic art - dramatic and musical - to subordinate his tragic gift, unique stage plasticity and deep musicality to a single artistic concept.

Since September 24, 1899, Chaliapin, the leading soloist of the Bolshoi and at the same time the Mariinsky theaters, has been touring abroad with triumphant success. In 1901, at La Scala in Milan, he sang the role of Mephistopheles in the opera of the same name by A. Boito with E. Caruso, conducted by A. Toscanini, with great success. The world fame of the Russian singer was confirmed by tours in Rome (1904), Monte Carlo (1905), Orange (France, 1905), Berlin (1907), New York (1908), Paris (1908), London (1913/14). The divine beauty of Chaliapin's voice captivated listeners from all countries. His high bass, delivered naturally, with a velvety, soft timbre, sounded full-blooded, powerful and possessed a rich palette of vocal intonations. The effect of artistic transformation amazed the listeners - it was not only the appearance, but also the deep inner content that was conveyed by the singer’s vocal speech. In creating capacious and scenically expressive images, the singer is helped by his extraordinary versatility: he is both a sculptor and an artist, writes poetry and prose. Such versatile talent of the great artist is reminiscent of the masters of the Renaissance - it is no coincidence that his contemporaries compared his opera heroes with Michelangelo's titans. Chaliapin's art crossed national boundaries and influenced the development of the world opera theater. Many Western conductors, artists and singers could repeat the words of the Italian conductor and composer D. Gavadzeni: “Chaliapin’s innovation in the field of dramatic truth of operatic art had a strong impact on the Italian theater... The dramatic art of the great Russian artist left a deep and lasting mark not only in the field of performance Russian operas by Italian singers, but in general, on the entire style of their vocal and stage interpretation, including the works of Verdi..."

"Chaliapin was attracted to characters strong people, embraced by an idea and passion, experiencing a deep spiritual drama, as well as bright, comedic images, notes D.N. Lebedev. - With stunning truthfulness and power, Chaliapin reveals the tragedy of the unfortunate father, distraught with grief, in “The Mermaid” or the painful mental discord and remorse experienced by Boris Godunov.

Sympathy for human suffering reveals high humanism - an integral property of progressive Russian art, based on nationality, on purity and depth of feelings. In this nationality, which filled Chaliapin’s entire being and entire work, the power of his talent, the secret of his persuasiveness and understandability to everyone, even an inexperienced person, is rooted.”

Chaliapin is categorically against feigned, artificial emotionality: “All music always expresses feelings in one way or another, and where there are feelings, mechanical transmission leaves the impression of terrible monotony. A spectacular aria sounds cold and protocol if the intonation of the phrase is not developed in it, if the sound is not colored with the necessary shades of experience. Western music also needs this intonation... which I recognized as mandatory for the transmission of Russian music, although it has less psychological vibration than Russian.”

Chaliapin is characterized by bright, intense concert activity. Listeners were invariably delighted with his performances of the romances “The Miller”, “The Old Corporal”, “The Titular Councilor” by Dargomyzhsky, “The Seminarist”, “Trepak” by Mussorgsky, “Doubt” by Glinka, “The Prophet” by Rimsky-Korsakov, “The Nightingale” by Tchaikovsky, “The Double” Schubert, “I am not angry”, “In a dream I cried bitterly” by Schumann.

Here's what I wrote about this side creative activity singer, a wonderful Russian musicologist, academician B. Asafiev:

“Chaliapin sang truly chamber music, sometimes with such concentration, so deeply that it seemed that he had nothing in common with the theater and never resorted to the emphasis on accessories and the appearance of expression required by the stage. Complete calm and restraint took possession of him. For example, I remember Schumann’s “In a Dream I Cried Bitterly” - one sound, a voice in silence, a modest, hidden emotion - but it’s as if the performer is not there, and this large, cheerful, clear person, generous with humor, affection, is not there. A lonely voice sounds - and everything is in the voice: all the depth and fullness of the human heart... The face is motionless, the eyes are extremely expressive, but in a special way, not like, say, Mephistopheles in the famous scene with the students or in the sarcastic serenade: there they burned angrily, mockingly, and here are the eyes of a man who felt the elements of grief, but understood that only in the severe discipline of the mind and heart - in the rhythm of all his manifestations - does a person gain power over both passions and suffering.”

The press loved to calculate the artist's fees, supporting the myth of Chaliapin's fabulous wealth and greed. So what if this myth is refuted by posters and programs of many charity concerts, and by the singer’s famous performances in Kyiv, Kharkov and Petrograd in front of huge working audiences? Idle rumors, newspaper rumors and gossip more than once forced the artist to take up his pen, refute sensations and speculation, and clarify the facts of his own biography. Useless!

During the First World War, Chaliapin's tours stopped. The singer opened two hospitals for wounded soldiers at his own expense, but did not advertise his “good deeds.” Lawyer M.F. Wolkenstein, who managed the singer’s financial affairs for many years, recalled: “If only they knew how much Chaliapin’s money passed through my hands to help those who needed it!”

After October revolution In 1917, Fyodor Ivanovich was engaged in the creative reconstruction of the former imperial theaters, was an elected member of the directors of the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theaters, and in 1918 directed the artistic part of the latter. In the same year, he was the first artist to be awarded the title of People's Artist of the Republic. The singer sought to get away from politics; in the book of his memoirs he wrote: “If I was anything in life, it was only an actor and singer; I was completely devoted to my calling. But least of all I was a politician.”

Outwardly, it might seem that Chaliapin’s life was prosperous and creatively rich. He is invited to perform at official concerts, he performs a lot for the general public, he is awarded honorary titles, asked to lead the work of various kinds of artistic juries and theater councils. But then there are sharp calls to “socialize Chaliapin”, “put his talent at the service of the people”, and doubts are often expressed about the singer’s “class loyalty”. Someone demands the mandatory involvement of his family in performing labor duties, someone makes direct threats to the former artist of the imperial theaters... “I saw more and more clearly that no one needed what I could do, that there was no point in my work.” , - the artist admitted.

Of course, Chaliapin could protect himself from the arbitrariness of zealous functionaries by making a personal request to Lunacharsky, Peters, Dzerzhinsky, and Zinoviev. But being in constant dependence on the orders of even such high-ranking officials in the administrative-party hierarchy is humiliating for an artist. Moreover, they often did not guarantee complete social security and certainly did not instill confidence in the future.

In the spring of 1922, Chaliapin did not return from his foreign tour, although for some time he continued to consider his non-return temporary. The home environment played a significant role in what happened. Caring for children and the fear of leaving them without a livelihood forced Fyodor Ivanovich to agree to endless tours. The eldest daughter Irina remained to live in Moscow with her husband and mother, Pola Ignatievna Tornagi-Chalyapina. Other children from the first marriage - Lydia, Boris, Fedor, Tatiana - and children from the second marriage - Marina, Marfa, Dassia and the children of Maria Valentinovna (second wife), Edward and Stella, lived with them in Paris. Chaliapin was especially proud of his son Boris, who, according to N. Benois, achieved “great success as a landscape and portrait painter.” Fyodor Ivanovich willingly posed for his son; The portraits and sketches of his father made by Boris “are priceless monuments to the great artist...”.

In foreign lands, the singer enjoyed constant success, touring almost all countries of the world - England, America, Canada, China, Japan, and the Hawaiian Islands. Since 1930, Chaliapin performed in the Russian Opera troupe, whose performances were famous high level staged culture. The operas “Rusalka”, “Boris Godunov”, “Prince Igor” had particular success in Paris. In 1935, Chaliapin was elected a member of the Royal Academy of Music (together with A. Toscanini) and was awarded an academician's diploma. Chaliapin's repertoire included about 70 parties. In the operas of Russian composers, he created unsurpassed in strength and life-truth images of the Miller (“Rusalka”), Ivan Susanin (“Ivan Susanin”), Boris Godunov and Varlaam (“Boris Godunov”), Ivan the Terrible (“The Woman of Pskov”) and many others . Among the best roles in Western European opera are Mephistopheles (Faust and Mephistopheles), Don Basilio (The Barber of Seville), Leporello (Don Giovanni), Don Quixote (Don Quixote). Chaliapin was equally great in chamber vocal performance. Here he introduced an element of theatricality and created a kind of “theater of romance.” His repertoire included up to four hundred songs, romances and works of chamber and vocal music of other genres. The masterpieces of performing arts included “The Flea”, “The Forgotten”, “Trepak” by Mussorgsky, “Night View” by Glinka, “The Prophet” by Rimsky-Korsakov, “Two Grenadiers” by R. Schumann, “The Double” by F. Schubert, as well as Russian folk songs “Farewell, joy”, “They don’t tell Masha to go beyond the river”, “Because of the island to the river”.

In the 20-30s he made about three hundred recordings. “I love gramophone recordings...” admitted Fyodor Ivanovich. “I am excited and creatively excited by the idea that the microphone symbolizes not a specific audience, but millions of listeners.” The singer was very picky about recordings; among his favorites was the recording of Massenet’s “Elegy,” Russian folk songs, which he included in his concert programs throughout creative life. According to Asafiev’s recollection, “the wide, powerful, inescapable breath of the great singer saturated the melody, and it was heard that there was no limit to the fields and steppes of our Motherland.”

On August 24, 1927, the Council of People's Commissars adopted a resolution depriving Chaliapin of the title of People's Artist. Gorky did not believe in the possibility of removing the title of People’s Artist from Chaliapin, about which rumors began to spread already in the spring of 1927: “The title of People’s Artist given to you by the Council of People’s Commissars can only be annulled by the Council of People’s Commissars, which he did not do, and, of course, not will do." However, in reality everything happened differently, not at all as Gorky expected...

Fyodor Ivanovich Chaliapin (b. 1873 - d. 1938) - great Russian Opera singer(bass).

Fyodor Chaliapin was born on February 1 (13), 1873 in Kazan. The son of the peasant of the Vyatka province Ivan Yakovlevich Chaliapin (1837-1901), a representative of the ancient Vyatka family of the Shalyapins (Shelepins). As a child, Chaliapin was a singer. Received an elementary education.

Chaliapin himself considered the beginning of his artistic career to be 1889, when he joined the drama troupe of V. B. Serebryakov. Initially, as a statistician.

On March 29, 1890, Chaliapin's first solo performance took place - the role of Zaretsky in the opera "Eugene Onegin", staged by the Kazan Society of Performing Art Lovers. Throughout May and the beginning of June 1890, Chaliapin was a chorus member of V. B. Serebryakov’s operetta company.

In September 1890, Chaliapin arrived from Kazan to Ufa and began working in the chorus of an operetta troupe under the direction of S. Ya. Semenov-Samarsky.

Quite by accident, I had to transform from a chorister into a soloist, replacing a sick artist in Moniuszko’s opera “Pebble.” This debut brought out the 17-year-old Chaliapin, who was occasionally assigned small opera roles, for example Fernando in Il Trovatore. The following year, Chaliapin performed as the Unknown in Verstovsky's Askold's Grave. He was offered a place in the Ufa zemstvo, but the Little Russian troupe of Dergach came to Ufa, and Chaliapin joined it. Traveling with her led him to Tiflis, where for the first time he managed to seriously practice his voice, thanks to the singer D. A. Usatov. Usatov not only approved of Chaliapin’s voice, but, due to the latter’s lack of financial resources, began giving him singing lessons for free and generally took a great part in it. He also arranged for Chaliapin to join the Tiflis opera of Forcatti and Lyubimov. Chaliapin lived in Tiflis for a whole year, performing the first bass parts in the opera.

In 1893 he moved to Moscow, and in 1894 to St. Petersburg, where he sang in Arcadia in Lentovsky's opera troupe, and in the winter of 1894/5 - in an opera company at the Panaevsky Theater, in Zazulin's troupe. The beautiful voice of the aspiring artist and especially his expressive musical recitation in connection with his truthful acting attracted the attention of critics and the public to him. In 1895, Chaliapin was accepted by the directorate of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theaters into the opera troupe: he entered the stage of the Mariinsky Theater and sang with success the roles of Mephistopheles (Faust) and Ruslan (Ruslan and Lyudmila). Chaliapin’s varied talent was also expressed in the comic opera “The Secret Marriage” by D. Cimaroz, but still did not receive due appreciation. It is reported that during the 1895-1896 season. he “appeared quite rarely and, moreover, in parties that were not very suitable for him.” The famous philanthropist S.I. Mamontov, who at that time owned an opera house in Moscow, was the first to notice Chaliapin’s extraordinary talent and persuaded him to join his private troupe. Here in 1896-1899. Chaliapin developed artistically and developed his stage talent, performing in a number of roles. Thanks to his subtle understanding of Russian music in general and modern music in particular, he completely individually, but at the same time deeply truthfully created a whole series of types in Russian operas. At the same time, he worked hard on roles in foreign operas; for example, the role of Mephistopheles in Gounod’s Faust in his broadcast received amazingly bright, strong and original coverage. Over the years, Chaliapin gained great fame.

Since 1899, he again served in the Imperial Russian Opera in Moscow (Bolshoi Theater), where he enjoyed enormous success. He was highly appreciated in Milan, where he performed at the La Scala theater in the title role of Mephistopheles A. Boito (1901, 10 performances). Chaliapin's tours in St. Petersburg on the Mariinsky stage constituted a kind of event in the St. Petersburg musical world.

During the revolution of 1905, he joined progressive circles and donated proceeds from his speeches to revolutionaries. His performances with folk songs(“Dubinushka” and others) sometimes turned into political demonstrations.

Since 1914 he has performed in the private opera companies of S. I. Zimin (Moscow) and A. R. Aksarin (Petrograd).

Since 1918 - artistic director of the Mariinsky Theater. Received the title of People's Artist of the Republic.

Chaliapin's long absence aroused suspicion and negative attitude in Soviet Russia; Thus, in 1926, Mayakovsky wrote in his “Letter to Gorky”: “Or should you live, / as Chaliapin lives, / with scented applause / daubed? / Come back / now / such an artist / back / to Russian rubles - / I will be the first to shout: / - Roll back, / People’s Artist of the Republic!” In 1927, Chaliapin donated the proceeds from one of his concerts to the children of emigrants, which was interpreted and presented as support for the White Guards. In 1928, by a resolution of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR, he was deprived of the title of People's Artist and the right to return to the USSR; this was justified by the fact that he did not want to “return to Russia and serve the people whose title of artist was awarded to him” or, according to other sources, by the fact that he allegedly donated money to monarchist emigrants.

In the spring of 1937, he was diagnosed with leukemia, and on April 12, 1938, he died in the arms of his wife. He was buried in the Batignolles cemetery in Paris.

On October 29, 1984, a ceremony for the reburial of the ashes of F.I. Chaliapin took place at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

The opening took place on October 31, 1986 tombstone the great Russian singer F. I. Chaliapin (sculptor A. Eletsky, architect Yu. Voskresensky).

Born into the family of peasant Ivan Yakovlevich from the village of Syrtsovo, who served in the zemstvo government, and Evdokia Mikhailovna from the village of Dudinskaya, Vyatka province.

At first little Fedor, trying to get them “to work”, they apprenticed to the shoemaker N.A. Tonkov, then V.A. Andreev, then to a turner, later to a carpenter.

IN early childhood He developed a beautiful treble voice and often sang with his mother. At the age of 9, he began singing in a church choir, where he was brought by the regent Shcherbitsky, their neighbor, and began to earn money from weddings and funerals. The father bought a violin for his son at a flea market and Fyodor tried to play it.

Later Fedor entered the 6th city four-year school, where there was a wonderful teacher N.V. Bashmakov, who graduated with a diploma of commendation.

In 1883, Fyodor Chaliapin went to the theater for the first time and continued to strive to watch all the performances.

At the age of 12, he began participating in the performances of the touring troupe as an extra.

In 1889 he joined the drama troupe of V.B. Serebryakov as a statistician.

On March 29, 1890, Fyodor Chaliapin made his debut as Zaretsky in the opera by P.I. Tchaikovsky's "Eugene Onegin", staged by the Kazan Society of Performing Art Lovers. Soon he moves from Kazan to Ufa, where he performs in the choir of the troupe S.Ya. Semenov-Samarsky.

In 1893, Fyodor Chaliapin moved to Moscow, and in 1894 to St. Petersburg, where he began singing in the Arcadia country garden, at the V.A. Panaev and in the troupe of V.I. Zazulina.

In 1895, the directorate of the St. Petersburg Opera Houses accepted him into the troupe of the Mariinsky Theater, where he sang the roles of Mephistopheles in Faust by C. Gounod and Ruslan in Ruslan and Lyudmila by M.I. Glinka.

In 1896, S.I. Mamontov invited Fyodor Chaliapin to sing in his Moscow private opera and move to Moscow.

In 1899, Fyodor Chaliapin became the leading soloist of the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow and, while touring, performed with great success at the Mariinsky Theater.

In 1901, Fyodor Chaliapin gave 10 triumphant performances at La Scala in Milan, Italy, and went on a concert tour throughout Europe.

Since 1914, he began performing in private opera companies of S.I. Zimin in Moscow and A.R. Aksarina in Petrograd.

In 1915, Fyodor Chaliapin played the role of Ivan the Terrible in the film drama “Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible” based on the drama “The Pskov Woman” by L. Mey.

In 1917, Fyodor Chaliapin acted as a director, directing Bolshoi Theater opera by D. Verdi “Don Carlos”.

After 1917, he was appointed artistic director of the Mariinsky Theater.

In 1918, Fyodor Chaliapin was awarded the title of People's Artist of the Republic, but in 1922 he went on tour to Europe and remained there, continuing to perform successfully in America and Europe.

In 1927, Fyodor Chaliapin donated money to a priest in Paris for the children of Russian emigrants, which was presented as help “to the White Guards in the fight against Soviet power” on May 31, 1927 in the magazine “Vserabis” by S. Simon. And on August 24, 1927, the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR, by decree, deprived him of the title of People's Artist and forbade him to return to the USSR. This resolution was canceled by the Council of Ministers of the RSFSR on June 10, 1991 “as unfounded.”

In 1932, he starred in the film “The Adventures of Don Quixote” by G. Pabst based on the novel by Cervantes.

In 1932 -1936 Fyodor Chaliapin went on tour to the Far East. He gave 57 concerts in China, Japan, and Manchuria.

In 1937 he was diagnosed with leukemia.

On April 12, 1938, Fedor died and was buried in the Batignolles cemetery in Pargis in France. In 1984, his ashes were transferred to Russia and on October 29, 1984, they were reburied at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.