The image and characteristics of Sharikov, Bulgakov’s dog’s heart, essay. The story "Heart of a Dog": characteristics of Sharikov

Consider the image of Sharikov from the story " dog's heart". In this work, Bulgakov does not just talk about an unnatural experiment. Mikhail Afanasyevich describes a new type of person who appeared not in the scientist’s laboratory, but in Soviet reality in the post-revolutionary years. An allegory of this type is the image of Sharikov in the story “The Heart of a Dog.” The basis of the work is the relationship between the great scientist and Sharikov, a man artificially created from a dog.

Assessment of life by the dog Sharik

The first part of this story is based largely on the internal monologue of a stray half-starved dog. He evaluates street life in his own way, gives a description of the characters, morals, and life of Moscow during the NEP era with many teahouses, shops, taverns on Myasnitskaya with clerks who hated dogs. Sharik is able to appreciate affection and kindness, and sympathize. He, oddly enough, understands the social structure of the new country well. Sharik condemns the new masters of life, but knows about Preobrazhensky, an old intellectual from Moscow, that he will not “kick” a hungry dog.

Implementation of Preobrazhensky's experiment

In the life of this dog, a happy accident occurs, in her opinion - a professor takes her to his luxurious apartment. It has everything, even a few “extra rooms”. However, the professor does not need the dog for fun. He wants to carry out a fantastic experiment: after transplanting a certain part, a dog will have to turn into a human. If Preobrazhensky becomes Faust, creating a man in a test tube, then his second father, who gave Sharik his pituitary gland, is Klim Petrovich Chugunkin. Bulgakov very briefly characterizes this man. His profession is playing around taverns on the balalaika. He is poorly built, the liver is dilated as a result of drinking alcohol. Chunugkin died in a pub from a stab in the heart. The creature that appeared after the operation inherited the essence of its second father. Sharikov is aggressive, swaggering, insolent.

Polygraph Poligrafovich Sharikov

Mikhail Afanasyevich created a vivid image of Sharikov in the story “Heart of a Dog”. This hero is devoid of ideas about culture, about how to behave with other people. After some time, a conflict brews between the creation and the creator, Polygraph Poligrafovich Sharikov, who calls himself a “homunculus,” and Preobrazhensky. The tragedy is that a “man” who has barely learned to walk finds reliable allies in his life. They provide a revolutionary theoretical basis for all his actions. One of them is Shvonder. Sharikov learns from this hero about what privileges he, a proletarian, has in comparison with Preobrazhensky, a professor. In addition, he begins to understand that the scientist who gave him a second life is a class enemy.

Sharikov's behavior

Let’s add a few more touches to the image of Sharikov in Bulgakov’s story “The Heart of a Dog.” This hero clearly understands the main credo of the new masters of life: steal, plunder, steal what others have created, and most importantly, strive for equalization. And the dog, once grateful to Preobrazhensky, no longer wants to put up with the fact that the professor settled “alone in seven rooms.” Sharikov brings a paper according to which he should be allocated an area of 16 square meters in the apartment. m. Morality, shame, and conscience are alien to the polygraph. He lacks everything else except anger, hatred, meanness. He's getting looser and looser every day. Polygraph Poligrafovich commits outrages, steals, drinks, and molests women. This is the image of Sharikov in the story “Heart of a Dog”.

The finest hour of Polygraph Poligrafovich Sharikov

The new job becomes his finest hour. A former stray dog makes a dizzying leap. She turns into the head of the department for cleaning Moscow from stray animals. This choice of profession by Sharikov is not surprising: people like them always want to destroy their own. However, Polygraph does not stop there. New details complement the image of Sharikov in the story “Heart of a Dog.” Short description His further actions are as follows.

The story of the typist, the reverse transformation

Sharikov appears some time later in Preobrazhensky’s apartment with a young girl and says that he is signing with her. This is a typist from his department. Sharikov declares that Bormental will need to be evicted. In the end, it turns out that he deceived this girl and made up many stories about himself. The last thing Sharikov does is inform on Preobrazhensky. The sorcerer-professor from the story that interests us manages to turn a man back into a dog. It’s good that Preobrazhensky realized that nature does not tolerate violence against itself.

Sharikovs in real life

IN real life, alas, balls are much more durable. Arrogant, self-confident, with no doubt that everything is permitted to them, these semi-literate lumpen people have brought our country to a deep crisis. This is not surprising: violence over the course of historical events and disregard for the laws of social development could only give birth to the Sharikovs. The polygraph in the story turned back into a dog. But in life he managed to go a long and, as it seemed to him and suggested to others, a glorious path. He poisoned people in the 30-50s, just like once stray animals were once in his line of work. He carried suspicion and dog anger throughout his entire life, replacing with them dog loyalty, which had become unnecessary. This hero, having entered rational life, remained at the level of instincts. And he wanted to change the country, the world, the universe in order to make it easier to satisfy these animal instincts. All these ideas are conveyed by the creator of the image of Sharikov in the story “Heart of a Dog.”

Human or animal: what distinguishes ballers from other people?

Sharikov is proud of his low origins and his lack of education. In general, he is proud of everything low that is in him, since only this raises him high above those who stand out in mind and spirit. People like Preobrazhensky need to be trampled into the dirt so that Sharikov can rise above them. The Sharikovs outwardly do not differ in any way from other people, but their non-human essence is waiting for the right moment. When it comes, such creatures turn into monsters, waiting for the first opportunity to seize their prey. This is their true face. The Sharikovs are ready to betray their own. For them, everything holy and lofty turns into its opposite when they touch it. The worst thing is that such people managed to achieve considerable power. Having come to her, the non-human strives to dehumanize everyone around him so that it becomes easier to manage the herd. All human feelings are repressed from them

Sharikovs today

It is impossible not to turn to modern times when analyzing the image of Sharikov in the story “Heart of a Dog.” Short essay According to the work, the final part should contain a few words about today's ballgames. The fact is that after the revolution in our country all the conditions were created for the emergence a large number of similar people. The totalitarian system greatly contributes to this. They have penetrated all areas public life, they still live among us. The Sharikovs are able to exist, no matter what. The main threat to humanity today is the heart of a dog along with the human mind. Therefore, the story, written at the beginning of the last century, remains relevant today. It is a warning to future generations. It sometimes seems that Russia has become different during this time. But the way of thinking, the stereotypes, will not change in 10 or 20 years. It will take more than one generation before the Sharikovs disappear from our lives, and people become different, devoid of animal instincts.

So, we looked at the image of Sharikov in the story “Heart of a Dog”. Summary works will help you get to know this hero better. And after reading the original story, you will discover some details of this image that we have omitted. The image of Sharikov in the story by M.A. Bulgakov's "Heart of a Dog" is a great artistic achievement of Mikhail Afanasyevich, like the entire work as a whole.

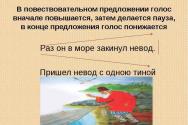

Let's consider speech characteristics Sharikova. Sharikov clearly and simply expresses his thoughts in simple sentences- this demonstrates his ethics. Most often expressed in short remarks: “What’s the matter! It’s a simple matter,” “What am I, a convict?”, “I don’t want to be a deserter,” “Du... gu-gu!”, “I’m not a gentleman, the gentlemen are all in Paris.”

Sharikov has no consistency in the construction of judgments; neighboring concepts are connected in his speech by a probable, causeless connection, which testifies to his ethics (as opposed to logic). Presence in speech introductory words: “Of course, how...we understand, sir! What kind of comrades we are to you! Where else! We didn’t study at universities, we didn’t live in fifteen-room apartments! Only now, maybe it’s time to leave it. Nowadays, everyone has their own right...” His assessments and judgments are subjective. There are comparative turnovers: “You have everything like it’s on parade, a napkin here, a tie here, yes, “excuse me,” and “please, merci,” but for real, that’s not the case. You are torturing yourself, just like during the tsarist regime.”

Sharikov talks about how a person should live, what rights he has. Persistently defends its interests: “For mercy, how can we do without a document? I'm really sorry. You know, a person without a document is strictly prohibited from existing.” Sharikov’s emotions are strong and colorful, he does not hold back expressing his emotions - he is irrational: “Yesterday cats were strangled, strangled...” Sharik is a pronounced sensory person, because he is a dog and perceives everything through his senses: eyes, ears, nose, tongue: “There is absolutely no need to learn to read when meat already smells a mile away,” “... the woman’s skirt smelled like lily of the valley.”

Author's characteristics

In order to fully determine the type to which Sharikov belongs, we will also analyze some of the author’s characteristics. For Sharikov The best way knowledge of the world - through the senses, which confirms its sensory nature: “He contemplated his shoes, and this gave him great pleasure,” “Sharikov poured the contents of the glass into his throat, wrinkled his face, brought a piece of bread to his nose, sniffed it, and then swallowed it, and his eyes filled with tears.”

Sharikov is quite secretive, restraining his feelings deep within himself, which only an attentive interlocutor can guess: "Sharikov in highest degree he took these words carefully and keenly, which was visible in his eyes.”

Sharikov is attracted to situations of new, unusual beginnings, cannot sit still, is always ready for activity: “Taking advantage of Bormenthal’s short absence, he took possession of his razor and ripped open his cheekbones so that Philip Philipovich and Dr. Bormental put stitches on the cut, causing Sharikov to howl for a long time, bursting into tears.”

Analysis of these characteristics showed that Sharikov is the complete opposite of Professor Preobrazhensky in all mental functions.

Description of personality type

Sharik and Sharikov are one hero. They are distinguished by the fact that Sharik is a dog, and Sharikov is the person that Sharik turned into after the operation. The dynamics from Sharik to Sharikov are such that Sharik is rational, and Sharikov is irrational, and at the same time they are both sensory-ethical introverts. Summarizing the results obtained, we compose the following table.

Subject of the work

At one time, M. Bulgakov’s satirical story caused a lot of talk. In “Heart of a Dog” the heroes of the work are bright and memorable; The plot is fantasy mixed with reality and subtext, in which sharp criticism of the Soviet regime is openly read. Therefore, the work was very popular in the 60s among dissidents, and in the 90s, after its official publication, it was even recognized as prophetic.

The theme of the tragedy of the Russian people is clearly visible in this work; in “Heart of a Dog” the main characters enter into an irreconcilable conflict with each other and will never understand each other. And, although the proletarians won in this confrontation, Bulgakov in the novel reveals to us the whole essence of the revolutionaries and their type of new man in the person of Sharikov, leading us to the idea that they will not create or do anything good.

There are only three main characters in “Heart of a Dog,” and the narrative is mainly told from Bormenthal’s diary and through the dog’s monologue.

Characteristics of the main characters

Sharikov

A character who appeared as a result of an operation from the mongrel Sharik. A transplant of the pituitary gland and gonads of the drunkard and rowdy Klim Chugunkin turned a sweet and friendly dog into Poligraf Poligrafych, a parasite and a hooligan.

Sharikov embodies all the negative traits of the new society: he spits on the floor, throws cigarette butts, does not know how to use the restroom and constantly swears. But this is not even the worst thing - Sharikov quickly learned to write denunciations and found a calling in killing his eternal enemies, cats. And while he deals only with cats, the author makes it clear that he will do the same with people who stand in his way.

Bulgakov saw this base power of the people and a threat to the entire society in the rudeness and narrow-mindedness with which the new revolutionary government resolves issues.

Professor Preobrazhensky

An experimenter who uses innovative developments in solving the problem of rejuvenation through organ transplantation. He is a famous world scientist, a respected surgeon, whose “speaking” surname gives him the right to experiment with nature.

I was used to living in grand style - servants, a house of seven rooms, luxurious dinners. His patients are former nobles and high revolutionary officials who patronize him.

Preobrazhensky is a respectable, successful and self-confident person. The professor, an opponent of any terror and Soviet power, calls them “idlers and idlers.” He considers affection the only way to communicate with living beings and denies the new government precisely for its radical methods and violence. His opinion: if people are accustomed to culture, then the devastation will disappear.

The rejuvenation operation yielded an unexpected result - the dog turned into a human. But the man turned out to be completely useless, uneducable and absorbing the worst. Philip Philipovich concludes that nature is not a field for experiments and he interfered with its laws in vain.

Dr. Bormenthal

Ivan Arnoldovich is completely and completely devoted to his teacher. At one time, Preobrazhensky took an active part in the fate of a half-starved student - he enrolled him in the department, and then took him on as an assistant.

The young doctor tried in every possible way to develop Sharikov culturally, and then completely moved in with the professor, as it became more and more difficult to cope with the new person.

The apotheosis was the denunciation that Sharikov wrote against the professor. At the climax, when Sharikov took out a revolver and was ready to use it, it was Bromenthal who showed firmness and toughness, while Preobrazhensky hesitated, not daring to kill his creation.

The positive characterization of the heroes of “Heart of a Dog” emphasizes how important honor and self-respect. Bulgakov described himself and his doctor-relatives in many of the same traits as both doctors, and in many ways would have acted the same way as them.

Shvonder

The newly elected chairman of the house committee, who hates the professor as a class enemy. This is a schematic hero, without deep reasoning.

Shvonder completely bows to the new revolutionary government and its laws, and in Sharikov he sees not a person, but a new useful unit of society - he can buy textbooks and magazines, participate in meetings.

Sh. can be called Sharikov’s ideological mentor; he tells him about his rights in Preobrazhensky’s apartment and teaches him how to write denunciations. The chairman of the house committee, due to his narrow-mindedness and lack of education, always hesitates and gives in in conversations with the professor, but this makes him hate him even more.

Other heroes

The list of characters in the story would not be complete without two au pairs - Zina and Daria Petrovna. They recognize the superiority of the professor, and, like Bormenthal, are completely devoted to him and agree to commit a crime for the sake of their beloved master. They proved this at the time of the repeated operation to transform Sharikov into a dog, when they were on the side of the doctors and accurately followed all their instructions.

You have become acquainted with the characteristics of the heroes of Bulgakov’s “Heart of a Dog,” a fantastic satire that anticipated the collapse of Soviet power immediately after its emergence - the author, back in 1925, showed the whole essence of those revolutionaries and what they were capable of.

Work test

Such a literary hero as Sharikov’s “Heart of a Dog” cannot leave the reader indifferent. His image in the story outrages, shocks, causes a storm of emotions, this is the merit of the author - a genius artistic word M. Bulgakov. The creature, which appeared due to human intervention in what Mother Nature commands, serves as a reminder to humanity of its mistakes.

Appearance of Polygraph Sharikov

The author's irony affected not only the semantic component of Sharikov's image, but also his appearance. The creature, which was born as a result of the operation of Professor Philip Preobrazhensky, is a kind of symbiosis of a dog and a person. The animal was transplanted with the pituitary gland and seminal glands of the criminal and drunkard Klim Chugunkin.

The latter died in a fight, which speaks about the lifestyle of a man who became an unwitting participant in the operation. The author emphasizes that the human being into which the dog Sharik turned after the operation looks very much like a dog. His hair, body hair, gaze, habits - everything indicates that the animal is invisibly present in the image of the newly made “citizen”.

Sharikov's too low forehead indicates his low intelligence. Bright, flashy details in clothing are an indicator of bad taste and lack of basic culture in clothing.

The moral character of the hero

Sharikov is a symbol of arrogance, impudence, rudeness, familiarity, illiteracy, laziness. His image is the personification of the lumpen proletariat: that layer of society that very quickly got used to the new political conditions. Relying on fragmentary information, altering phrases from the slogans of the new government, these people “fight” for their rights, pretending to be active and work. In fact, they are parasites and opportunists; the government, which promises unprecedented benefits, attracts stupid, narrow-minded people who are ready to be a blind instrument in the fight for a bright future.

Polygraph Poligrafovich inherits the worst that is in the nature of animals and humans. The dog's loyalty and devotion, his gratitude to the owner - all this disappeared during the first two weeks of Sharikov's life. The character bites, pesters women, and is rude to everyone indiscriminately. The hero's ingratitude, his dissatisfaction with everything, and the lack of minimal culture in communication are infuriating. He begins to demand registration from the professor, and after some time he tries to evict Philip Philipovich. As a result, it comes to the point that Sharikov decides to kill his creator. This moment is very symbolic, endowed with a special meaning. It is here that the motive of the political ideology of the new system is clearly visible.

The fate of Polygraph Sharikov

No matter how hard the professor tried to educate and remake his brainchild, Sharikov turned out to be beyond the influence of convictions and moral teachings. Even violence (or the threat of it from the professor's assistant) has no effect on Sharikov. The hero continues to lead an immoral lifestyle, use foul language, scare residents, and drink. The characters are too intelligent to change anything. Sharikov and others like him understand only brute force, they live according to the principle of existence in the animal world.

The most amazing thing is that after the professor corrects the mistake, the hero comes to an important conclusion. In the creature that resulted from the experiment, all the worst things come from humans; the dog is a kind and noble animal. It turns out that there are people who are worse than dogs - this metaphorical nature is emphasized by the author several times. Fortunately, the professor was able to correct his mistake in time. He has the courage to admit that his philosophy of nonviolence does not always work without fail. Bulgakov hints that the new political system will not be able to repeat the professor’s step. The course of history cannot be stopped, and retribution for interfering with natural processes will inevitably overtake society.

“HEART OF A DOG”: good Sharik and bad Sharikov

"Heart of a Dog" was written after "Fatal Eggs" in January - March 1925. The story could not pass censorship. What was it about her that frightened the Bolshevik authorities so much?

The editor of "Nedra" Nikolai Semenovich Angarsky (Klestov) hurried Bulgakov to create "The Heart of a Dog", hoping that it would have no less success among the reading public than "Fatal Eggs". On March 7, 1925, Mikhail Afanasyevich read the first part of the story at the literary meeting of the Nikitin Subbotniks, and on March 21, the second part there. One of the listeners, M.L. Schneider, conveyed to the audience his impression of “Heart of a Dog” as follows: “This is the first literary work, which dares to be itself. The time has come to realize the attitude towards what happened” (i.e. to the October Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent stay of the Bolsheviks in power).

At these same readings, an attentive OGPU agent was present, who, in reports dated March 9 and 24, assessed the story completely differently:

“I was at the next literary “subbotnik” with E.F. Nikitina (Gazetny, 3, apt. 7, t. 2–14–16). Bulgakov read his new story. Plot: a professor removes the brains and seminal glands from a person who has just died and puts them into a dog, resulting in the “humanization” of the latter. Moreover, the whole thing is written in hostile tones, breathing endless contempt for the Soviet Union:

1) The professor has 7 rooms. He lives in a workhouse. A deputation from workers comes to him with a request to give them 2 rooms, because the house is overcrowded, and he alone has 7 rooms. He responds with a demand to give him an 8th as well. Then he goes to the phone and at No. 107 declares to some very influential co-worker “Vitaly Vlasievich” (in the surviving text of the first edition of the story this character is called Vitaly Alexandrovich; in subsequent editions he turned into Pyotr Alexandrovich; probably the informant incorrectly wrote down his middle name by ear. - B.S.), that he will not perform the operation on him, “stops the practice altogether and leaves forever for Batum,” because workers armed with revolvers came to him (and this in fact is not the case) and forced him to sleep in the kitchen , and perform operations in the restroom. Vitaly Vlasievich calms him down, promising to give him a “strong” piece of paper, after which no one will touch him.

The professor is triumphant. The working delegation is left with its nose. “Then buy, comrade,” says the worker, “literature for the benefit of the poor of our faction.” “I won’t buy it,” the professor answers.

"Why? After all, it's inexpensive. Only 50 kopecks. Maybe you don’t have any money?“

“No, I have money, but I just don’t want it.”

“So, you don’t love the proletariat?”

“Yes,” the professor admits, “I don’t like the proletariat.”

All this is heard to the accompaniment of malicious laughter from Nikitin’s audience. Someone can’t stand it and angrily exclaims: “Utopia.”

2) “Devastation,” the same professor grumbles over a bottle of Saint-Julien. - What it is? An old woman barely walking with a stick? Nothing like this. There is no devastation, there has not been, there will not be and there is no such thing as devastation. The devastation is the people themselves.

I lived in this house on Prechistenka from 1902 to 1917 for fifteen years. There are 12 apartments on my stairs. You know how many patients I have. And downstairs on the front door there was a coat hanger, galoshes, etc. So what do you think? During these 15 years, not a single coat or rag has ever gone missing. This was the case until February 24 (the day the February Revolution began - B.S.), and on the 24th everything was stolen: all the fur coats, my 3 coats, all the canes, and even the doorman’s samovar was whistled. That's what. And you say devastation." Deafening laughter from the entire audience.

3) The dog he adopted tore his stuffed owl. The professor flew into indescribable rage. The servant advises him to give the dog a good beating. The professor’s rage does not subside, but he thunders: “It’s impossible. You can't hit anyone. This is terror, and this is what they achieved with their terror. You just need to teach.” And he fiercely, but not painfully, pokes the dog’s muzzle at the torn owl.

4) “The best remedy for health and nerves is not to read newspapers, especially Pravda.” I saw 30 patients in my clinic. So what do you think, those who have not read Pravda recover faster than those who have read it,” etc., etc. A great many more examples could be given, examples of the fact that Bulgakov definitely hates and despises the entire Sovstroy, denies everything his achievements.

In addition, the book is replete with pornography, dressed up in a businesslike, supposedly scientific form. Thus, this book will please both the malicious man in the street and the frivolous lady, and will sweetly tickle the nerves of just a depraved old man. There is a faithful, strict and vigilant guardian of the Soviet Power, this is Glavlit, and if my opinion does not disagree with his, then this book will not see the light of day. But let me note the fact that this book (its first part) has already been read to an audience of 48 people, 90 percent of whom are writers themselves. Therefore, her role, her main work has already been done, even if she is not missed by Glavlit: she has already infected the literary minds of listeners and sharpened their feathers. And the fact that it will not be published (if “it won’t be”) will be a luxurious lesson for them, these writers, for the future, a lesson on how not to write in order to be missed by the censor, that is, how publish your beliefs and propaganda, but so that it sees the light of day. (25/III 25 Bulgakov will read the 2nd part of his story.)

My personal opinion: such things, read in the most brilliant Moscow literary circle, are much more dangerous than the useless and harmless speeches of 101st grade writers at meetings of the “All-Russian Union of Poets.”

An unknown informant reported on Bulgakov’s reading of the second part of the story much more succinctly. Either she made less of an impression on him, or he considered that the main thing had already been said in the first denunciation:

“The second and last part of Bulgakov’s story “The Heart of a Dog” (I told you about the first part two weeks earlier), which he finished reading at the “Nikitinsky Subbotnik”, caused strong indignation of the two communist writers who were there and the general delight of everyone else. The content of this final part boils down to approximately the following: the humanized dog began to become impudent every day, more and more. She became depraved: she made vile proposals to the professor’s maid. But the center of the author's mockery and accusation is based on something else: on the dog wearing a leather jacket, on the demand for living space, on the manifestation of a communist way of thinking. All this infuriated the professor, and he immediately put an end to the misfortune he himself had created, namely: he turned the humanized dog into his former, ordinary dog.

If similarly crudely disguised attacks (since all this “humanization” is just an emphatically noticeable, careless make-up) attacks appear on the book market of the USSR, then the White Guard abroad, exhausted no less than us from book hunger, and even more from the fruitless search for an original, biting plot , one can only envy the exceptional conditions for counter-revolutionary authors in our country.”

This kind of message probably alerted the authorities that controlled the literary process, and made the ban on “Heart of a Dog” inevitable. People experienced in literature praised the story. For example, on April 8, 1925, Veresaev wrote to Voloshin: “I was very pleased to read your review of M. Bulgakov... his humorous things are pearls, promising him to be an artist of the first rank. But censorship cuts it mercilessly. Recently I stabbed the wonderful piece “Heart of a Dog,” and he is completely losing heart.”

On April 20, 1925, Angarsky complained in a letter to Veresaev that satirical works It is very difficult to carry Bulgakov through censorship. I’m not sure that his new story “Heart of a Dog” will pass. In general, literature is bad. The censorship does not adopt the party line.” The old Bolshevik Angarsky is pretending to be naive here.

In fact, the country began to gradually tighten censorship as Stalin strengthened his power.

The reaction of critics to Bulgakov’s previous story “Fatal Eggs,” considered as an anti-Soviet pamphlet, also played a role. On May 21, 1925, Nedra employee B. Leontiev sent Bulgakov a very pessimistic letter: “Dear Mikhail Afanasyevich, I am sending you “Notes on Cuffs” and “Heart of a Dog.” Do with them what you want. Sarychev in Glavlit said that “Heart of a Dog” is no longer worth cleaning. “The whole thing is unacceptable” or something like that.” However, N.S. Angarsky, who really liked the story, decided to turn to the very top - to Politburo member L.B. Kamenev. Through Leontyev, he asked Bulgakov to send the manuscript of “The Heart of a Dog” with censorship corrections to Kamenev, who was vacationing in Borjomi, with a covering letter, which should be “the author’s, tearful, with an explanation of all the ordeals...”

On September 11, 1925, Leontyev wrote to Bulgakov about the disappointing outcome: “Your story “Heart of a Dog” was returned to us by L.B. Kamenev. At Nikolai Semenovich’s request, he read it and expressed his opinion: “This is a sharp pamphlet on modernity, under no circumstances should it be printed.” Leontiev and Angarsky reproached Bulgakov for sending Kamenev an uncorrected copy: “Of course, one cannot give of great importance two or three of the sharpest pages; they could hardly change anything in the opinion of such a person as Kamenev. And yet, it seems to us that your reluctance to provide the previously corrected text played a sad role here.” Subsequent events showed the groundlessness of such fears: the reasons for the banning of the story were much more fundamental than a few uncorrected pages or corrected in accordance with censorship requirements. On May 7, 1926, as part of a campaign sanctioned by the Central Committee to combat “smenovekhism,” Bulgakov’s apartment was searched and the manuscript of the writer’s diary and two copies of the typescript of “The Heart of a Dog” were confiscated. Only more than three years later, with the assistance of Gorky, what was confiscated was returned to the author.

The plot of “The Heart of a Dog,” like “Fatal Eggs,” goes back to Wells’s work, this time to the novel “The Island of Doctor Moreau,” where a maniac professor in his laboratory on a desert island is engaged in the surgical creation of unusual “hybrids” of humans and animals . Wells's novel was written in connection with the rise of the anti-vivisection movement - operations on animals and their killing for scientific purposes. The story also contains the idea of rejuvenation, which became popular in the 1920s in the USSR and a number of European countries.

Bulgakov's kindest professor Philip Filippovich Preobrazhensky conducts an experiment to humanize the cute dog Sharik and very little resembles Wells's hero. But the experiment ends in failure. The ball only perceives worst traits his donor, the drunkard and hooligan proletarian Klim Chugunkin. Instead of good dog an ominous, stupid and aggressive Polygraph Poligrafovich Sharikov arises, who, nevertheless, fits perfectly into socialist reality and even makes an enviable career: from an indefinite being social status to the head of the department for cleaning Moscow from stray animals. Probably, having turned his hero into the head of a subdepartment of the Moscow public utilities, Bulgakov commemorated with an unkind word his forced service in the Vladikavkaz subdepartment of arts and the Moscow Lito (literary department of the Glavpolitprosvet). Sharikov becomes socially dangerous, incited by the chairman of the house committee Shvonder against his creator - Professor Preobrazhensky, writes denunciations against him, and in the end even threatens him with a revolver. The professor has no choice but to return the newly-minted monster to its primitive dog state.

If in " Fatal eggs“A disappointing conclusion was made about the possibility of realizing the socialist idea in Russia given the existing level of culture and education, then in “Heart of a Dog” the attempts of the Bolsheviks to create a new man, called upon to become the builder of a communist society, are parodied. In his work “At the Feast of the Gods,” first published in Kyiv in 1918, the philosopher, theologian and publicist S.N. Bulgakov noted: “I confess to you that comrades sometimes seem to me to be creatures completely devoid of spirit and possessing only lower mental abilities, special a species of Darwin's ape - Homo socialisticus." Mikhail Afanasyevich, in the image of Sharikov, materialized this idea, probably taking into account the message of V.B. Shklovsky, the prototype of Shpolyansky in “The White Guard,” given in the memoir “Sentimental Journey” about monkeys who allegedly fight with the Red Army soldiers.

Homo socialisticus turned out to be surprisingly viable and fit perfectly into the new reality. Bulgakov foresaw that the Sharikovs could easily drive away not only the Preobrazhenskys, but also the Shvonders. The strength of Polygraph Poligrafovich lies in his virginity in relation to conscience and culture. Professor Preobrazhensky sadly prophesies that in the future there will be someone who will set Sharikov against Shvonder, just as today the chairman of the house committee sets him against Philip Philipovich. The writer seemed to predict the bloody purges of the 30s already among the communists themselves, when some Shvonders punished others, less fortunate. Shvonder is a gloomy, although not devoid of comedy, personification of the lowest level of totalitarian power - the house manager, opens a large gallery of similar heroes in Bulgakov’s work, such as Allelujah (Burtle) in “Zoyka’s Apartment”, Bunsha in “Bliss” and “Ivan Vasilyevich”, Nikanor Ivanovich Bosoy in The Master and Margarita.

There is also a hidden anti-Semitic subtext in “Heart of a Dog”. In the book by M.K. Diterichs “The Murder of the Royal Family” there is the following description of the chairman of the Ural Council Alexander Grigorievich Beloborodov (in 1938 he was successfully shot as a prominent Trotskyist): “He gave the impression of an uneducated, even semi-literate person, but he was proud and very big about own opinions. Cruel, loud, he came to the fore among a certain group of workers even under the Kerensky regime, during the period of the notorious work of political parties to “deepen the revolution.” Among the blind masses of workers, he enjoyed great popularity, and the dexterous, cunning and intelligent Goloshchekin, Safarov and Voikov (Diterichs considered all three to be Jews, although disputes about the ethnic origin of Safarov and Voikov continue to this day. - B.S.) skillfully took advantage of this popularity, flattering his rude pride and pushing him forward constantly and everywhere. He was a typical Bolshevik from among the Russian proletariat, not so much in idea as in the form of manifestation of Bolshevism in crude, brutal violence, which did not understand the limits of nature, an uncultured and unspiritual being.”

Sharikov is exactly the same creature, and the chairman of the house committee, the Jew Shvonder, guides him. By the way, his surname may have been constructed by analogy with the surname Shinder. It was worn by the commander of the special detachment mentioned by Diterichs, who accompanied the Romanovs from Tobolsk to Yekaterinburg.

A professor with the priestly surname Preobrazhensky performs the operation on Sharik on the afternoon of December 23, and the humanization of the dog is completed on the night of January 7, since the last mention of his canine appearance in the observation diary kept by Bormental’s assistant is dated January 6. Thus, the entire process of turning a dog into a human covers the period from December 24 to January 6, from Catholic to Orthodox Christmas Eve. A Transfiguration is taking place, but not the Lord's. The new man Sharikov is born on the night of January 6th to 7th - in Orthodox Christmas. But Poligraf Poligrafovich is not the incarnation of Christ, but the devil, who took his name in honor of a fictitious “saint” in the new Soviet “saints” that prescribe the celebration of Printer’s Day. Sharikov is, to some extent, a victim of printed products - books outlining Marxist dogmas, which Shvonder gave him to read. From there " new person“I only came up with the thesis about primitive leveling - “take everything and divide it.”

During his last quarrel with Preobrazhensky and Bormental, Sharikov’s connection with otherworldly forces is emphasized in every possible way:

“Some kind of unclean spirit possessed Poligraf Poligrafovich, obviously, death was already watching over him and fate stood behind him. He himself threw himself into the arms of the inevitable and barked angrily and abruptly:

What is it really? Why can't I find any justice for you? I am sitting here on sixteen arshins and will continue to sit!

Get out of the apartment,” Philip Philipovich whispered sincerely.

Sharikov himself invited his death. He raised his left hand and showed Philip Philipovich a bitten pine cone with an unbearable cat smell. And then with his right hand, directed at the dangerous Bormental, he took a revolver out of his pocket.”

Shish is the standing “hair” on the devil’s head. Sharikov’s hair is the same: “coarse, like bushes in an uprooted field.” Armed with a revolver, Poligraf Poligrafovich is a unique illustration of the famous saying of the Italian thinker Niccolo Machiavelli: “All armed prophets have won, but the unarmed ones have perished.” Here Sharikov is a parody of V.I. Lenin, L.D. Trotsky and other Bolsheviks, who ensured the triumph of their teachings in Russia by military force. By the way, the three volumes of Trotsky’s posthumous biography, written by his follower Isaac Deutscher, were called: “The Armed Prophet”, “The Disarmed Prophet”, “The Expelled Prophet”. Bulgakov's hero is not a prophet of God, but of the devil. However, only in the fantastic reality of the story is it possible to disarm him and, through a complex surgical operation, bring him to primary view- a kind and sweet dog Sharik, who only hates cats and janitors. In reality, no one was able to disarm the Bolsheviks.

The real prototype of Professor Philip Filippovich Preobrazhensky was Bulgakov's uncle Nikolai Mikhailovich Pokrovsky, one of whose specialties was gynecology. His apartment at Prechistenka, 24 (or Chisty Lane, 1) coincides in detail with the description of Preobrazhensky’s apartment. It is interesting that in the address of the prototype, the names of the street and alley are associated with Christian tradition, and his surname (in honor of the Feast of the Intercession) corresponds to the surname of the character associated with the Feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord.

On October 19, 1923, Bulgakov described his visit to the Pokrovskys in his diary: “Late in the evening I went to see the guys (N.M. and M.M. Pokrovsky. - B.S.). They became nicer. Uncle Misha read my last story “Psalm” the other day (I gave it to him) and asked me today what I wanted to say, etc. They already have more attention and understanding that I am engaged in literature.”

The prototype, like the hero, was subjected to compaction, and, unlike Professor Preobrazhensky, N.M. Pokrovsky was unable to avoid this unpleasant procedure. On January 25, 1922, Bulgakov noted in his diary: “They brought a couple into Uncle Kolya’s house by force in his absence... contrary to all decrees....”

A colorful description of N.M. Pokrovsky has been preserved in the memoirs of Bulgakov’s first wife T.N. Lapp: “... As soon as I started reading (“Heart of a Dog.” - B.S.) I immediately guessed that it was him. Just as angry, he was always humming something, his nostrils flared, his mustache was just as bushy. In general, he was nice. He was then very offended by Mikhail for this. He had a dog for a while, a Doberman pinscher.” Tatyana Nikolaevna also claimed that “Nikolai Mikhailovich did not marry for a long time, but he really loved to look after women.” Perhaps this circumstance prompted Bulgakov to force the bachelor Preobrazhensky to engage in operations to rejuvenate aging ladies and gentlemen eager for love affairs.

Bulgakov’s second wife, Lyubov Evgenievna Belozerskaya, recalled: “The scientist in the story “Heart of a Dog” is professor-surgeon Philip Filippovich Preobrazhensky, whose prototype was Uncle M.A. - Nikolai Mikhailovich Pokrovsky, brother of the writer’s mother, Varvara Mikhailovna... Nikolai Mikhailovich Pokrovsky, gynecologist, former assistant to the famous professor V.F. Snegirev, lived on the corner of Prechistenka and Obukhov Lane, a few houses from our dovecote. His brother, a general practitioner, dear Mikhail Mikhailovich, a bachelor, lived right there. Two nieces also found shelter in the same apartment... He (N.M. Pokrovsky. - B.S.) was distinguished by a hot-tempered and unyielding character, which gave rise to one of the nieces to joke: “You can’t please Uncle Kolya, he says: don’t you dare.” give birth and don’t you dare have an abortion.”

Both Pokrovsky brothers took advantage of all their numerous female relatives. On Winter St. Nicholas everyone gathered at the birthday table, where, in the words of M.A., “the birthday boy himself sat like a certain god of hosts.” His wife, Maria Silovna, put pies on the table. A silver ten-kopeck piece was baked in one of them. The finder was considered especially lucky, and they drank to his health. The God of Hosts loved to tell a simple anecdote, distorting it beyond recognition, which caused the laughter of the young cheerful company.”

When writing the story, Bulgakov consulted both him and his friend from Kyiv times, N.L. Gladyrevsky. L.E. Belozerskaya painted the following portrait of him in her memoirs: “We often visited our Kiev friend M.A., a friend of the Bulgakov family, surgeon Nikolai Leonidovich Gladyrevsky. He worked at Professor Martynov’s clinic and, returning to his place, visited us along the way. M.A. I always talked with him with pleasure... Describing the operation in the story “Heart of a Dog”, M.A. I turned to him for some surgical clarifications. He... showed Mack to Professor Alexander Vasilyevich Martynov, and he admitted him to his clinic and performed an operation for appendicitis. All this was resolved very quickly. I was allowed to go to M.A. immediately after surgery. He was so pitiful, such a wet chicken... Then I brought him food, but he was irritated all the time because he was hungry: in terms of food, he was limited.”

In the early editions of the story, very specific individuals could be discerned among Preobrazhensky’s patients. Thus, her frantic lover Moritz mentioned by the elderly lady is Bulgakov’s good friend Vladimir Emilievich Moritz, an art critic, poet and translator who worked at the State Academy artistic sciences(GAKHN) and enjoyed great success among the ladies. In particular, the first wife of Bulgakov's friend N.N. Lyamin, Alexandra Sergeevna Lyamina (née Prokhorova), the daughter of a famous manufacturer, left her husband for Moritz. In 1930, Moritz was arrested on charges of creating, together with the philosopher G. G. Shpet, who was well known to Bulgakov, a “strong citadel of idealism” at the State Academic Academy of Arts, exiled to Kotlas, and after returning from exile, he successfully taught acting in Theater School them. M.S. Shchepkina.

Moritz wrote a book of children's poems, Nicknames, and translated Shakespeare, Moliere, Schiller, Beaumarchais, and Goethe. In a later edition, the surname Moritz was replaced by Alphonse. The episode with the “famous public figure”, inflamed with passion for a fourteen-year-old girl, in the first edition was provided with such transparent details that it truly frightened N.S. Angarsky:

I am a famous public figure, professor! What to do now?

Gentlemen! - Philip Philipovich shouted indignantly. - You can’t do that! You need to restrain yourself. How old is she?

Fourteen, professor... You understand, publicity will ruin me. One of these days I should get a business trip to London.

But I’m not a lawyer, my dear... Well, wait two years and marry her.

I'm married, professor!

Ah, gentlemen, gentlemen!..”

Angarsky crossed out the phrase about the business trip to London in red, and noted the entire episode with a blue pencil, signing twice in the margin. As a result, in the subsequent edition, “well-known public figure” was replaced by “I’m too famous in Moscow...”, and the business trip to London turned into simply a “business trip abroad.” The fact is that the words about the public figure and London made the prototype easily identifiable. Until the spring of 1925, only two of the prominent figures of the Communist Party traveled to the British capital. The first - Leonid Borisovich Krasin, from 1920 was the People's Commissar of Foreign Trade and at the same time the plenipotentiary and trade representative in England, and from 1924 - the plenipotentiary in France. He nevertheless died in 1926 in London, where he was returned as plenipotentiary in October 1925. The second is Christian Georgievich Rakovsky, the former head of the Council of People's Commissars of Ukraine, who replaced Krasin as plenipotentiary representative in London at the beginning of 1924.

The action of Bulgakov's story takes place in the winter of 1924–1925, when Rakovsky was the plenipotentiary representative in England. But it was not he who served as the prototype of a child molester, but Krasin. Leonid Borisovich had a wife, Lyubov Vasilievna Milovidova, and three children. However, in 1920 or 1921, Krasin met in Berlin the actress Tamara Vladimirovna Zhukovskaya (Miklashevskaya), who was 23 years younger than him. Leonid Borisovich himself was born in 1870, therefore, in 1920 his mistress was 27 years old. But the public, of course, was shocked by the large age difference between the People's Commissar and the actress. Nevertheless, Miklashevskaya became Krasin’s common-law wife. He gave Miklashevskaya, who went to work at the People's Commissariat of Foreign Trade, his last name, and she began to be called Miklashevskaya-Krasina. In September 1923, she gave birth to a daughter, Tamara, from Krasin. These events in 1924 were, as they say, “well-known” and were reflected in “The Heart of a Dog,” and Bulgakov, in order to sharpen the situation, made the mistress of a “prominent public figure"Fourteen year old.

Krasin appeared several times in Bulgakov's diary. On May 24, 1923, in connection with Curzon’s sensational ultimatum, to which the feuilleton “Lord Curzon’s Benefit in “On the Eve”” was dedicated, the writer noted that “Curzon does not want to hear about any compromises and demands from Krasin (who, after the ultimatum, immediately ran off to London by airplane) exact execution of the ultimatum.” Here I immediately remember the drunkard and libertine Styopa Likhodeev, also a member of the nomenklatura, although lower than Krasin - just a “red director”. Stepan Bogdanovich, according to financial director Rimsky, went from Moscow to Yalta on some kind of super-fast fighter (in fact, Woland sent him there). But Likhodeev returns to Moscow as if on an airplane.

Another entry is related to Krasin’s arrival in Paris and is dated on the night of December 20-21, 1924: “The arrival of Monsieur Krasin was marked by the stupidest story in “style russe”: a crazy woman, either a journalist or an erotomaniac, came to Krasin’s embassy with a revolver - fire. The police inspector immediately took her away. She didn’t shoot anyone, and overall it’s a petty, bastard story. I had the pleasure of meeting this Dixon either in ’22 or ’23 in the lovely editorial office of “Nakanune” in Moscow, on Gnezdnikovsky Lane. Fat, completely crazy woman. She was released abroad by Pere Lunacharsky, who was fed up with her advances.”

It is quite possible that Bulgakov connected the failed attempt on Krasin’s life by the crazy literary lady Maria Dixon-Evgenieva, née Gorchakovskaya, with rumors about Krasin’s scandalous relationship with Miklashevskaya.

IN diary entry on the night of December 21, 1924, in connection with the cooling of Anglo-Soviet relations after the publication of a letter from Zinoviev, the then head of the Comintern, Bulgakov also mentioned Rakovsky: “Zinoviev’s famous letter, which contains unequivocal calls for the indignation of workers and troops in England, is not only by the Foreign Office, but also by the whole of England, apparently, is unconditionally recognized as genuine. England is finished. The stupid and slow Englishmen, albeit belatedly, are still beginning to realize that in Moscow, Rakovsky and couriers arriving with sealed packages, there lurks a certain, very formidable danger of the disintegration of Britain.”

Bulgakov sought to demonstrate the moral corruption of those who were called upon to work for the decay of “good old England” and “beautiful France.” Through the lips of Philip Philipovich, the author expressed surprise at the incredible voluptuousness of the Bolshevik leaders. The love affairs of many of them, in particular the “all-Union elder” M.I. Kalinin and the secretary of the Central Executive Committee A.S. Enukidze, were not a secret for the Moscow intelligentsia in the 20s.

In the early edition of the story, Professor Preobrazhensky’s statement that the galoshes from the hallway “disappeared in April 1917” was also read more seditiously - an allusion to Lenin’s return to Russia and his “April Theses” as the root cause of all the troubles that happened in Russia. In subsequent editions, April was replaced for censorship reasons by February 1917, and the source of all disasters was the February Revolution.

One of the most famous passages in “Heart of a Dog” is Philip Philipovich’s monologue about devastation: “This is a mirage, smoke, fiction!.. What is this “devastation” of yours? Old woman with a stick? The witch who broke all the windows and put out all the lamps? Yes, it doesn’t exist at all! What do you mean by this word? This is this: if, instead of operating, I start singing in chorus every evening in my apartment, I will be in ruins. If, while going to the restroom, I start, excuse me for the expression, urinating past the toilet and Zina and Daria Petrovna do the same, the restroom will be in chaos. Consequently, the devastation is not in the closets, but in the heads.” It has one very specific source. In the early 20s, Valery Yazvitsky’s one-act play “Who is to blame?” was staged at the Moscow Workshop of Communist Drama. (“Devastation”), where the main actor there was an ancient, crooked old woman in rags named Destruction, who was making it difficult for the proletarian family to live.

Soviet propaganda really made some kind of mythical, elusive villain out of the devastation, trying to hide that the root cause was the Bolshevik policy, war communism, and the fact that people had lost the habit of working honestly and efficiently and had no incentive to work. Preobrazhensky (and with him Bulgakov) recognizes that the only cure against devastation is ensuring order, when everyone can mind their own business: “Policeman! This, and only this! And it doesn’t matter at all whether he wears a badge or a red cap. Place a policeman next to every person and force this policeman to moderate the vocal impulses of our citizens. I'll tell you... that nothing will change for the better in our house, or in any other house, until you pacify these singers! As soon as they stop their concerts, the situation will naturally change for the better!” Bulgakov punished lovers of choral singing during working hours in the novel “The Master and Margarita”, where the employees of the Entertainment Commission are forced to sing non-stop by the former regent Koroviev-Fagot.

The condemnation of the house committee, which instead of its direct duties is engaged in choral singing, may have its source not only from Bulgakov’s experience of living in a “bad apartment”, but also from Dieterichs’ book “The Murder of the Royal Family.” It is mentioned there that “when Avdeev (commandant of the Ipatiev House - B.S.) left in the evening, Moshkin (his assistant - B.S.) gathered his friends from the security, including Medvedev, into the commandant’s room, and here They began a drinking binge, drunken hubbub and drunken songs that lasted until late at night.

They usually shouted fashionable revolutionary songs at the top of their voices: “You fell a victim in the fatal struggle,” or “Let us renounce the old world, shake its ashes from our feet,” etc.” Thus, the persecutors of Preobrazhensky were likened to regicides.

And the policeman as a symbol of order appears in the feuilleton “Capital in a Notebook.” The myth of devastation turns out to be correlated with the myth of S.V. Petliura in “The White Guard,” where Bulgakov reproaches the former accountant for the fact that he ultimately went about his business - he became the “chief ataman” of the ephemeral, in the writer’s opinion, Ukrainian state. In the novel, Alexei Turbin’s monologue, where he calls for a fight against the Bolsheviks in the name of restoring order, is correlated with Preobrazhensky’s monologue and evokes a reaction similar to it. Brother Nikolka notes that “Alexey is an irreplaceable person at the rally, a speaker.” Sharik thinks about Philip Philipovich, who has entered into oratorical fervor: “He could earn money right at rallies...”

The very name “Heart of a Dog” is taken from a tavern couplet placed in A.V. Leifert’s book “Balagans” (1922):

...For the second pie -

Frog legs filling,

With onions, peppers

Yes, with a dog's heart.

This name can be correlated with past life Klim Chugunkin, who earned his living playing the balalaika in taverns (ironically, Bulgakov’s brother Ivan also earned his living in exile).

The program of Moscow circuses, which Preobrazhensky is studying for the presence of acts with cats that are contraindicated for Sharik (“Solomonovsky ... has four of some kind ... ussems and a dead center man ... Nikitin ... elephants and the limit of human dexterity”) exactly corresponds to the real circumstances of the beginning of 1925 . It was then that aerialists “Four Ussems” and tightrope walker Eton, whose It was called "Man at Dead Point".

According to some reports, even during Bulgakov’s lifetime, “Heart of a Dog” was distributed in samizdat. An anonymous correspondent writes about this in a letter dated March 9, 1936. Also, the famous literary critic Razumnik Vasilievich Ivanov-Razumnik in his book of memoir essays “Writers' Fates” noted:

“Realizing too late, the censorship decided from now on not to let through a single printed line of this “inappropriate satirist” (as a certain guy who had a command at the censorship outpost put it about M. Bulgakov). Since then, his stories and tales have been prohibited (I read in manuscript his very witty story “Ball”)...”

Here, “Ball” clearly means “Heart of a Dog.”

“The Tale of a Dog’s Heart was not published for censorship reasons. I think that the work “The Tale of a Dog’s Heart” turned out to be much more malicious than I expected when creating it, and the reasons for the ban are clear to me. The humanized dog Sharik turned out, from the point of view of Professor Preobrazhensky, to be a negative type, since he fell under the influence of a faction (trying to soften the political meaning of the story, Bulgakov claims that negative traits Sharikov are due to the fact that he came under the influence of the Trotskyist-Zinovievist opposition, which was persecuted in the fall of 1926. However, in the text of the story there is no hint that Sharikov or his patrons sympathized with Trotsky, Zinoviev, the “labor opposition” or any opposition movement to the Stalinist majority. - B.S.). I read this work at the Nikitin Subbotniks, to the editor of Nedra, Comrade Angarsky, and in the circle of poets at Pyotr Nikanorovich Zaitsev and at the Green Lamp. There were 40 people in the “Nikitin Subbotniks”, 15 people in the “Green Lamp”, and 20 people in the circle of poets. I should note that I repeatedly received invitations to read this work in different places and refused them, because I understood that in my satire it's too salty in the sense of malice and the story arouses too close attention.

Question: Indicate the names of the people who participate in the “Green Lamp” circle.

Answer: I refuse for ethical reasons.

Question: Do you think there is a political undercurrent to “Heart of a Dog”?

Answer: Yes, there are political aspects that are in opposition to the existing system.”

The dog Sharik also has at least one funny literary prototype. In the second half of the 19th century, the humorous fairy tale of the Russian writer of German origin Ivan Semenovich Gensler, “The Biography of Vasily Ivanovich the Cat, Told by Himself,” was very popular. Main character story - the St. Petersburg cat Vasily, who lives on Senate Square, upon closer examination very much resembles not only the cheerful cat Behemoth (though, unlike Bulgakov's magic cat, Gensler's cat is not black, but red), but also the kind dog Sharik (in his canine form ).

Here, for example, is how Gensler's story begins:

“I come from ancient knightly families that became famous in the Middle Ages, during the Guelphs and Ghibellines.

My late father, if only he had wanted, could have obtained certificates and diplomas regarding our origin, but, firstly, it would have cost God knows what; and secondly, if you think about it sensibly, what do we need these diplomas for?.. Hang it in a frame, on the wall, under the stove (our family lived in poverty, I’ll tell you about this later).”

But, for comparison, here are Bulgakov’s Sharik’s thoughts about his own origins after he found himself in the warm apartment of Professor Preobrazhensky and ate the same amount in a week as he did in the last one and a half hungry months on the streets of Moscow: “I’m handsome. Perhaps an unknown incognito canine prince,” the dog thought, looking at the shaggy coffee dog with a contented muzzle, walking in the mirrored distances. “It is very possible that my grandmother sinned with the diver. That's why I look, there is a white spot on my face. Where does it come from, you ask? Philip Philipovich is a man with great taste, he will not take the first mongrel dog he comes across."

The cat Vasily talks about his poor lot: “Oh, if you only knew what it means to sit under the stove!.. What a horror it is!.. Litter, garbage, muck, there are whole legions of cockroaches all over the wall; and in the summer, in the summer, mothers are holy! - especially when it’s not easy for them to bake bread! I tell you, there is no way to endure it!.. You will leave, and only on the street will you breathe in clean air.

Poof...ffa!

And besides, there are various other inconveniences. Sticks, brooms, pokers and all sorts of other kitchen tools are usually shoved under the stove.

Just as soon as they grab your eyes, they will poke your eyes out... And if not that, then they will poke a wet mop into your eyes... All day then you wash, wash and sneeze... Or at least this too: you sit and philosophize, closing your eyes...

What if some evil devil manages to throw a ladle of boiling water over the cockroaches... After all, the stupid creature won’t look to see if there’s anyone there; You’ll jump out of there like crazy, and even if you apologize, you’re such a brute, but no: he’s still laughing. Speaks:

Vasenka, what’s wrong with you?..

Comparing our life with that of bureaucrats, who, with a ten-ruble salary, have to live just outside of dog kennels, you truly come to the conclusion that these people are out of their minds: no, they should try living under the stove for a day or two!”

In the same way, Sharik becomes a victim of the boiling water that was thrown into the trash by the “rag cook”, and similarly talks about the lower Soviet employees, only with direct sympathy for them, while in Vasily the cat this sympathy is covered with irony. At the same time, it is quite possible that the cook splashed boiling water without intending to scald Sharik, but he, like Vasily, sees evil intent in what happened:

“U-u-u-u-goo-goo-goo! Oh look at me, I'm dying.

The blizzard in the gateway howls at me, and I howl with it. I'm lost, I'm lost. A scoundrel in a dirty cap, the cook of the canteen serving normal meals for employees of the Central Council of the National Economy, splashed boiling water and scalded my left side. What a reptile, and also a proletarian. Oh my God, how painful it is! It was eaten to the bones by boiling water. Now I’m howling, howling, but howling can I help?

How did I bother him? Will I really eat the Council of the National Economy if I rummage through the trash? Greedy creature! Just look at his face someday: he’s wider across himself. Thief with a copper face. Ah, people, people. At noon the cap treated me to boiling water, and now it’s dark, about four o’clock in the afternoon, judging by the smell of onions from the Prechistensky fire brigade. Firemen eat porridge for dinner, as you know. But this is the last thing, like mushrooms. Familiar dogs from Prechistenka, however, told me that in the Neglinny restaurant “bar” they eat the usual dish - mushrooms, pican sauce for 3 rubles. 75 k. portion. This is not an acquired taste, it’s like licking a galosh... Oooh-ooh-ooh...

Janitors are the most vile scum of all proletarians. Human cleaning, the lowest category. The cook is different. For example, the late Vlas from Prechistenka. How many lives did he save? Because the most important thing during illness is to intercept the bite. And so, it happened, the old dogs say, Vlas would wave a bone, and on it there would be an eighth of meat on it. God bless him for being a real person, the lordly cook of Count Tolstoy, and not from the Council for Normal Nutrition. What they are doing there in Normal nutrition is incomprehensible to a dog’s mind. After all, they, the bastards, cook cabbage soup from stinking corned beef, and those poor fellows don’t know anything. They run, eat, lap.

Some typist receives four and a half chervonets for the IX category, well, however, her lover will give her fildepers stockings. Why, how much abuse does she have to endure for this phildepers? After all, he does not expose her in any ordinary way, but exposes her to French love. With... these French, just between you and me. Although they eat it richly, and all with red wine. Yes... The typist will come running, because you can’t go to a bar for 4.5 chervonets. She doesn’t even have enough for cinema, and cinema is the only consolation in life for a woman. He trembles, winces, and eats... Just think: 40 kopecks from two dishes, and both of these dishes are not worth five kopecks, because the caretaker stole the remaining 25 kopecks. Does she really need such a table? The top of her right lung is not in order, and she has a female disease on French soil, she was deducted from the service, fed rotten meat in the dining room, here she is, here she is... Runs into the gateway in lover's stockings. Her feet are cold, there is a draft in her stomach, because the fur on her is like mine, and she wears cold pants, just a lace appearance. Rubbish for a lover. Put her on flannel, try it, he’ll shout: how ungraceful you are! I'm tired of my Matryona, I'm tired of flannel pants, now my time has come. I am now the chairman, and no matter how much I steal, it’s all on the female body, on cancerous cervixes, on Abrau-Durso. Because I was hungry enough when I was young, it will be enough for me, but there is no afterlife.

I feel sorry for her, I feel sorry for her! But I feel even more sorry for myself. I’m not saying this out of selfishness, oh no, but because we really are not on an equal footing. At least she’s warm at home, but for me, but for me... Where am I going to go? Woo-oo-oo-oo!..

Whoop, whoop, whoop! Sharik, and Sharik... Why are you whining, poor thing? Who hurt you? Uh...

The witch, a dry blizzard, rattled the gates and hit the young lady on the ear with a broom. She fluffed up her skirt to her knees, exposed her cream stockings and a narrow strip of poorly washed lace underwear, strangled her words and covered up the dog.”

In Bulgakov, instead of a poor official, forced to huddle almost in a dog kennel, there is an equally poor employee-typist. Only they are capable of compassion for unfortunate animals.

Both Sharik and Vasily Ivanovich are subjected to bullying by the “proletariat”. The first is mocked by janitors and cooks, the second by couriers and watchmen. But in the end, both find good patrons: Sharik is Professor Preobrazhensky, and Vasily Ivanovich, as it seemed to him at first glance, is the family of a shopkeeper who does not mock him, but feeds him, in the unrealistic hope that the lazy Vasily Ivanovich will catch mice. However, Gensler's hero leaves his benefactor in the finale and gives him a derogatory description:

“Forgive me,” I told him as I was leaving, you are a kind man, a glorious descendant of the ancient Varangians, with your ancient Slavic laziness and dirt, with your clay bread, with your rusty herrings, with your mineral sturgeon, with your carriage Chukhon oil, with your rotten eggs, with your tricks, weighting and attribution, and finally, your godly belief that your rotten goods are first grade. And I part with you without regret. If I ever encounter specimens like you on the long path of my life, I will run away into the forests. It is better to live with animals than with such people. Goodbye!"

Bulgakov’s Sharik is truly happy at the end of the story: “...The thoughts in the dog’s head flowed coherently and warmly.

“I’m so lucky, so lucky,” he thought, dozing off, “simply indescribably lucky.” I established myself in this apartment. I am absolutely sure that my origin is unclean. There is a diver here. My grandmother was a slut, may the old lady rest in heaven. True, for some reason they cut my head all over, but it will heal before the wedding. We have nothing to look at.”

From the book How to Write a Brilliant Novel by Frey James NSymbols: bad, good, ugly A symbol can be called an object that, in addition to the main one, also carries an additional semantic load. Suppose you are describing a cowboy who rides a horse and chews beef jerky. Beef jerky is a food. She is not a symbol

From the book Abolition of Slavery: Anti-Akhmatova-2 author Kataeva Tamara From the book Volume 3. Soviet and pre-revolutionary theater author Lunacharsky Anatoly VasilievichGood performance* Yesterday I was able to attend a performance at the Demonstration Theater. For the second time, Shakespeare's drama "Measure for Measure" was performed.1 This drama was extremely unlucky, despite the fact that the genius of Pushkin guessed its beauty and reflected it in his semi-translation poem "Angelo". Play

From the book All works school curriculum on literature in summary. 5-11 grade author Panteleeva E. V.“The Heart of a Dog” (Story) Retelling 1 In a cold and dank gateway, a homeless dog suffered from hunger and pain in his scalded side. He recalled how the cruel cook scalded his side, thought about delicious sausage scraps and watched the typist running about her business. Dog

From the book Outside the Window author Barnes Julian PatrickFord's The Good Soldier The back cover of Vintage's 1950 novel The Good Soldier was poignant. A group of "fifteen distinguished critics" praised Ford Madox Ford's 1915 novel. All of them

From the book Collection of critical articles by Sergei Belyakov author Belyakov SergeyBad good writer Olesha

From the book 100 greats literary heroes[with illustrations] author Eremin Viktor NikolaevichPolygraph Poligrafovich Sharikov A brilliant playwright, a talented fiction writer, but a superficial, very weak thinker, Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov spent his whole life trying to take a place that was not his in Russian literature. He tried to become bigger than he actually was, apparently.

From the book Literature 9th grade. Textbook-reader for schools with in-depth study of literature author Team of authorsMikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov Heart of a Dog It is difficult to imagine another writer of the 20th century whose work would so naturally and harmoniously unite with the traditions of such diverse Russian writers as Pushkin and Chekhov, Gogol and Dostoevsky. M. A. Bulgakov left rich and

From the book Movement of Literature. Volume I author Rodnyanskaya Irina BentsionovnaHamburg hedgehog in the fog Something about bad good literature Where does art go when it is freed from hands? Maria Andreevskaya What to do? Where to go? What to do? Unknown... Nikita