The originality of language in the story “Lefty”. Linguistic features of tale N

The linguistic features of the tale “Lefty” were the subject of study of our work. The structure of our work - description linguistic changes in different sections of the language, although it should immediately be noted that this classification is very relative, because some language changes can be attributed to several sections at once (however, like many phenomena modern language). The purpose of the work is to study the work of N. S. Leskov “Lefty” (The Tale of the Tula Oblique Lefty and the Steel Flea) for its linguistic features, to identify word usages unusual for the modern Russian language at all language levels and, if possible, to find explanations for them.

2. The reasons for the occurrence of inconsistencies in word usage in N. S. Leskov’s tale “Lefty” and the modern Russian language. The first reason - “The Tale of the Tula Oblique Lefty and the Steel Flea” was published in 1881. The second reason is genre feature. A tale is, according to V.V. Vinogradov’s definition, “an artistic orientation toward an oral monologue of a narrative type; it is an artistic imitation of monologue speech.” The third reason is that the sources of N. S. Leskov’s language were ancient secular and church books and historical documents. "On my own behalf I speak with the tongue old fairy tales and church-folk in purely literary speech,” said the writer.

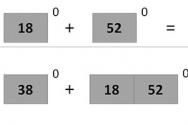

Colloquial expressions: - “...so they watered without mercy,” that is, they beat. - “...will distract you with something...”, that is, distract you. - “Aglitsky masters” Replacement of letters: - busters - chandeliers - ceramides - pyramids - buffa - bay Words with folk etymology, most often formed by combining words: - waterproof cables - waterproof clothing - small scale - microscope + fine - multiplication dowel - table + chisel - storm gauges (barometers) - measure + storm

Obsolete words and forms of words. The participle “servant” as a noun from the lost verb “serve”: “... pointed to the servant’s mouth.” An outdated form of the adverb “once” instead of “however.” (Like Pushkin’s “far away”: “far away it thundered: hurray”). "They'll get together in pairs." (“...and they envy her (the weaver and the cook) the sovereign’s wife” A.S. Pushkin). “...they run and run and don’t look back” (it should be “running”).

Word formation. Use of the prefix VZ- (as a feature of the book style): - “swung” - swaggered; - “shook up” with his shoulders – moved - “overcoming” from the verb “overcome”; - “counter” - one who goes towards - “medium” – from the middle: “Don’t drink little, don’t drink much, but drink moderately.” Words that exist in the language, but with a different meaning: “they called from the opposite pharmacy,” that is, the pharmacy opposite; “...in the middle there is a factory in it (the flea)” (a mechanism, something that starts, not in the sense of “enterprise”

Phonetic features: - “ears” instead of “ears”, the text presents the old form, non-palatalized; Syntax: - “..I’ll try to find out what your tricks are”; - “...wanted to have a spiritual confession..” Textual criticism: - “...no emergency holidays” (special); “...wants a detailed intention to discover about the girl...” Paronyms: “... Nikolai Pavlovich was terribly so... memorable” (instead of “memorable”) Tautology: “.. with one delight of feelings.” Oxymoron: “tight mansion.”

SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL CONFERENCE

"FIRST STEPS INTO SCIENCE"

LANGUAGE FEATURES OF N. S. LESKOV’S TALE “LEFT-HANDED.”

Completed by a student of grade 8 "G" MOBU secondary school No. 4

Mayatskaya Anastasia.

(Scientific adviser)

Dostoevsky's equal - he is a missed genius.

Igor Severyanin.

Any subject, any activity, any work seems uninteresting to a person if it is not clear. The work of Nikolai Semenovich Leskov “Lefty” is not very popular among seventh graders. Why? I think because it is complex and incomprehensible to schoolchildren of this age. And when you start to think about it, figure it out, assume and get to the bottom of the truth, the most interesting moments open up. And personally, it now seems to me that the story “Lefty” is one of the most extraordinary works of Russian literature, in the linguistic structure of which so much is hidden for a modern schoolchild...

The linguistic features of the story “Lefty” were subject of study our work. We tried to deal with every word usage unusual for the modern Russian language, and, if possible, find the reasons for the differences. We had to track this kind of changes in all sections of the language: phonetics, morphemics, morphology, syntax, punctuation, spelling, spelling. This is what it's all about structure our work is a description of linguistic changes in different sections of the language, although it should be noted right away that this classification is very relative, because some language changes can be attributed to several sections at once (however, like many phenomena of modern language).

So , target work - study the work “Lefty” (The Tale of the Tula Oblique Lefty and the Steel Flea) for its linguistic features, identify word usages unusual for the modern Russian language at all language levels and, if possible, find explanations for them.

2. The reasons for the occurrence of inconsistencies in word usage in the tale “Lefty” and the modern Russian language.

“The Tale of the Tula Oblique Lefty and the Steel Flea” was published in 1881. It is clear that significant changes have occurred in the language over 120 years - and this first reason the appearance of discrepancies with modern norms of word usage.

The second is a genre feature. “Lefty” entered the treasury of Russian literature also because it brought to perfection such a stylistic device as the skaz.

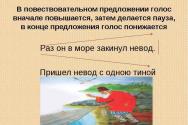

A tale is, by definition, “an artistic orientation towards an oral monologue of a narrative type; it is an artistic imitation of monologue speech.” If you think about the definition, it will become obvious that a work of this genre is characterized by a mixture of spoken (“oral monologue”) and book (“artistic imitation”) speech.

“Skaz”, as a word in the Russian language, clearly originated from the verb “skazat”, the full meaning of which is perfectly explained by: “speak”, “explain”, “notify”, “say” or “bayat”, that is, the skaz style goes back to folklore It is closer not to literary, but to colloquial speech (which means it is used a large number of colloquial word forms, words of so-called folk etymology). The author, as it were, is eliminated from the narrative and reserves the role of recording what he hears. (Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka is in this style). In "Lefty" the imitation of oral monologue speech is carried out at all levels of language, Leskov is especially inventive in word creation. And this The second reason discrepancies with modern literary norms.

Sources artistic language The writer's experiences are varied - they are primarily associated with his stock of life observations, deep acquaintance with the life and language of various social groups. The sources of the language were ancient secular and church books and historical documents. “On my own behalf, I speak in the language of ancient fairy tales and church folk in purely literary speech,” said the writer. In his notebook, Leskov records ancient Russian words and expressions that interested him for their expressiveness, which he later uses in the text of works of art. Thus, in the texts of the works, the author also used Old Russian and Church Slavonic word forms, rooted in the distant linguistic past. And this third reason discrepancies between language word forms in Leskov’s work and modern ones.

Igor Severyanin, also distinguished by his unusual word-creation, once wrote a sonnet dedicated to him. There were lines:

Dostoevsky's equal, he is a missed genius.

Enchanted wanderer of the catacombs of language!

It is through these catacombs of language in Leskov’s work “Lefty” that I suggest you go.

VOCABULARY.

Turning to popular vernacular, colloquial language, folk expressions, using words with folk etymology, Leskov tries to show that Russian folk speech is extremely rich, talented, and expressive.

Obsolete words and forms of words.

The text of the work “Lefty,” of course, is unusually rich in archaisms and historicisms (chubuk, postilion, kazakin, erfix (sobering drug), talma...), but any modern edition contains the necessary number of footnotes and explanations of such words, so that every student can read them on one's own. We were more interested obsolete forms of words:

Adjective comparative degree more useful, that is, more useful;

The participle “servant” as a noun from the lost verb “serve”: “... showed to the servant on the mouth."

The short participle of “blankets” (that is, dressed) from the disappeared blanket.

The participle “hosha”, formed from the verb “to want” (with the modern suffix –sh-, by the way)

The use of the word “although” instead of the modern “though”: “Now if I had Although there is one such master in Russia..."

The case form “on digits” is not a mistake: along with the word “digit”, there also existed the now obsolete (with a touch of irony) form “tsifir”.

Obsolete form of the adverb " alone" instead of "however".(Like " far away burst out: hurray "y).

The appearance of the so-called prosthetic consonant “v” between vowels

(“right-wingers") was characteristic of the Old Russian language in order to eliminate the unusual phenomenon of gaping (confluence of vowels).

Colloquial expressions:

-“...a glass of sour milk choked out";

-“..great I’m driving”, that is, quickly

-“...so watered without mercy,” that is, they beat.

-“...something will take..." that is, it will distract.

-“...smoked without stop"

Pubel poodle

Tugament instead of document

Kazamat - casemate

Symphon - siphon

Grandevu - rendezvous

Schiglets = boots

Washable – washable

Half skipper-sub skipper

Puplection - apoplexy (stroke)

Words with folk zytymology, most often formed by combining words.

Coach two-seater– a combination of the words “double” and “sit down”

The text shows fluctuations in the gender of nouns, which is typical of the literary norm of that time: “. .shutter slammed"; and unusual, erroneous forms: “his by force did not hold back,” that is, the instrumental case is declined according to the masculine model, although the nominative case is a feminine noun.

Mixing case forms. The word “look” can be used both with nouns in V. p. and with nouns in R. p.., Leskov mixed these forms: “... in different states miracles look."

- “Everything here is in your sight,” and provide.”, that is, “view”.

- “... Nikolai Pavlovich was terrible... memorable." (instead of “memorable”)

- “...they look at the girl without hiding, but with all relatedness.”(relatives)

-“...so that not a single minute for the Russian usefulness didn’t disappear” (benefits)

Inversion:

- “...now very angry.”

- “...you will have something worthy of presenting to the sovereign’s splendor.”

Mixing styles (colloquial and bookish):

- “...I want to go to my native place as soon as possible, because otherwise I might get a form of insanity.”

-“...no emergency holidays” (special)

- “...wants a detailed intention to discover about the girl...”

-“..from here with the left-hander and foreign species have come.”

-“...we’re going to look at their weapons cabinet, there are such nature of perfection"

- “...every person has everything for himself absolute circumstances It has". In addition, the use of such a form of the predicate verb is not typical of the Russian language (as, for example, English; and it is the English that the hero is talking about).

-“.. I don’t know now , for what need Is this kind of repetition happening to me?

Conclusion.

As can be seen from the above examples, changes have occurred at all levels of language. I believe that having become familiar with at least some of them, seventh graders will not only receive new information, but will also be very interested in reading the work “Lefty.”

For example, we suggested that our classmates work with examples from the “Vocabulary” section, here you can show your ingenuity, your linguistic flair, and no special preparation is required. Having explained several variants of words with folk etymology, they offered to figure out the rest on their own. The students were interested in the work.

And I would like to end my research with the words of M. Gorky: “Leskov is also a wizard of words, but he did not write plastically, but told stories, and in this art he has no equal. His story is an inspired song, simple, purely Great Russian words, descending one after another into intricate lines, sometimes thoughtfully, sometimes laughingly, ringing, and you can always hear in them a reverent love for people...”

1.Introduction (relevance of the topic, structure of the work, purpose of the study).

2. Reasons for the occurrence of inconsistencies in word usage in the work “Lefty” and in the modern Russian language.

3. Study of the language features of the tale “Lefty” at all levels:

Vocabulary;

Morphology;

Word formation;

Phonetics;

Textual criticism;

Syntax and punctuation;

Spelling.

4. Conclusion.

References.

1. . Novels and stories, M.: AST Olimp, 1998

2. . . Historical grammar of the Russian language.-M.: Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1963

3. . Dictionary living Great Russian language (1866). Electronic version.

The originality of the language in the story 8220 Lefty 8221

Story by N.S. Leskov’s “Lefty” is a special work. The author’s idea arose from a folk joke about how “the British made a flea out of steel, but our Tula people shod it and sent it back.” Thus, the story initially assumed closeness to folklore not only in content, but also in the manner of narration. The style of “Lefty” is very unique. Leskov managed to bring the genre of the story as close as possible to oral folk art, namely to skaz, while at the same time preserving certain features of a literary author's story.

The originality of the language in the story “Lefty” is manifested primarily in the very manner of narration. The reader immediately gets the feeling that the narrator was directly involved in the events described. This is important for understanding the main ideas of the work, because the emotionality of the main character makes you worry with him, the reader perceives a somewhat subjective view of the actions of other characters in the story, but it is this subjectivity that makes them as real as possible, the reader himself is transported to those distant times.

In addition, the fairy-tale style of narration serves as a clear sign that the narrator is a simple person, a hero from the people. He expresses not only his thoughts, feelings and experiences, behind this generalized image stands the entire working Russian people, living from hand to mouth, but caring about the prestige of their native country. With the help of descriptions of views on the life of gunsmiths and craftsmen through the eyes not of an outside observer, but of a sympathetic fellow, Leskov raises an eternal problem: why the fate of the common people, who feed and clothe the entire upper class, is indifferent to those in power, why are craftsmen remembered only when they need to support “prestige of the nation”? Bitterness and anger can be heard in the description of Lefty's death, and the author especially clearly shows the contrast between the fate of the Russian master and the English half-skipper, who found themselves in a similar situation.

However, in addition to the tale-like manner of narration, one can note the rather widespread use of vernacular in the story. For example, in the descriptions of the actions of Emperor Alexander I and the Cossack Platov, such colloquial verbs appear as “to ride” and “to jerk”. This not only once again demonstrates the narrator’s closeness to the people, but also expresses his attitude towards the authorities. People understand perfectly well that their pressing problems do not concern the emperor at all, but they do not get angry, but come up with naive excuses: Tsar Alexander, in their understanding, is the same simple person, he may want to change the life of the province for the better, but he is forced to deal with more important matters. The absurd order to conduct “internecine negotiations” is put by the narrator into the mouth of Emperor Nicholas with secret pride, but the reader guesses Leskov’s irony: the naive artisan is trying his best to show the significance and importance of the imperial personality and does not suspect how much he is mistaken. Thus, a comic effect arises from the incongruity of overly pompous words.

Also, the stylization under foreign words, the narrator with the same proud expression speaks about Platov’s “aspiration”, about how the flea “dances,” but he doesn’t even realize how stupid it sounds. Here Leskov again demonstrates naivety ordinary people, but besides this, this episode conveys the spirit of the times, when sincere patriotism still hid a secret desire to be like enlightened Europeans. A particular manifestation of this is remodeling for native language names of works of art that are too inconvenient for a Russian person, for example, the reader learns about the existence of Abolon Polvedersky and is again surprised in equal measure by both the resourcefulness and, again, the naivety of the Russian peasant.

Even Russian words must be used in a special way by fellow Lefty; he again, with an important and sedate look, reports that Platov “could not quite” speak French, and authoritatively notes that “he doesn’t need it: he’s a married man.” This is an obvious verbal alogism, behind which lies the author’s irony, caused by the author’s pity for the man, and, moreover, the irony is sad.

From the point of view of the uniqueness of the language, special attention is drawn to neologisms caused by ignorance of the thing that the man is talking about. These are words such as “busters” (chandelier plus bust) and “melkoskop” (so named, apparently, according to the function it performs). The author notes that in the minds of the people, objects of lordly luxury have merged into an incomprehensible tangle, people do not distinguish busts from chandeliers, they are so in awe of their senseless pompousness of palaces. And the word “melkoskop” became an illustration of another idea of Leskov: Russian masters are wary of the achievements of foreign science, their talent is so great that no technical inventions will defeat the master’s genius. However, at the same time, in the finale, the narrator sadly notes that machines have nevertheless supplanted human talent and skill.

The originality of the language of the story “Lefty” lies in the manner of narration, in the use of vernacular and neologisms. With the help of these literary techniques, the author managed to reveal the character of Russian craftsmen; the reader is shown bright, original images of Lefty and the narrator.

The first writer who comes to his mind is, of course, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. The second portrait that appears before the inner gaze of the domestic bookworm is the face of Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. But there is one classic who, as a rule, is forgotten in this context (or not mentioned so often) - Nikolai Semenovich Leskov. Meanwhile, his works are also saturated with the “Russian spirit”, and they also reveal not only the features of the Russian national character, but also the specifics of all Russian life.

In this sense, Leskov’s story “Lefty” stands apart. It reproduces with extraordinary accuracy and depth all the flaws in the structure of domestic life and all the heroism of the Russian people. People, as a rule, now do not have time to read the collected works of Dostoevsky or Tolstoy, but they should find time to open a book on the cover of which it is written: N. S. Leskov “Lefty”.

Plot

The story supposedly begins in 1815. Emperor Alexander the First, on a voyage across Europe, also visits England. The British really want to surprise the Emperor, and at the same time show off the skills of their craftsmen, and for several days they take him around different rooms and show him all sorts of amazing things, but the main thing they have in store for the finale is a filigree work: a steel flea that can dance. Moreover, it is so small that without a microscope it is impossible to see it. Our king was very surprised, but his attendant - Don Cossack There are no boards at all. On the contrary, he kept bawling that ours could do no worse.

He soon died, and ascended the throne who accidentally discovered a strange thing and decided to check Platov’s words by sending him to visit the Tula masters. The Cossack arrived, instructed the gunsmiths and went home, promising to return in two weeks.

The masters, including Lefty, retired to the house of the main character of the tale and worked there for two weeks, until Platov returned. Local residents heard the constant knocking, but the craftsmen themselves never left Lefty’s house during this time. They became recluses until the work was done.

Platov arrives. They bring him the same flea in a box. He furiously throws the first craftsman he came across into the carriage (he turned out to be left-handed) and goes to St. Petersburg to see the Tsar “on the carpet.” Of course, Lefty did not get to the king right away; he was first beaten and kept in prison for a short time.

The flea appears before the bright eyes of the monarch. He looks and looks at her and cannot understand what the Tula people did. Both the sovereign and his courtiers struggled with the secret, then the Tsar-Father ordered to invite Lefty, and he told him that he should take and look not at the whole flea, but only at its legs. No sooner said than done. It turned out that the Tula people had shoed the English flea.

Immediately the wonder was returned to the British, and in words something like the following was conveyed: “We, too, can do something.” Here we will pause in the plot presentation and talk about what the image of Lefty is in the tale of N. S. Leskov.

Lefty: between the gunsmith and the holy fool

Lefty’s appearance testifies to his “superiority”: “he’s left-handed with an oblique look, the hair on his cheek and temples was torn out during training.” When Lefty arrived to the Tsar, he was also dressed in a very peculiar way: “in shorts, one trouser leg is in a boot, the other is dangling, and the leg is old, the hooks are not fastened, they are lost, and the collar is torn.” He spoke to the king as he was, without observing manners and without fawning, if not on an equal footing with the sovereign, then certainly without fear of power.

People who are at least a little interested in history will recognize this portrait - this is a description of the ancient Russian holy fool; he was never afraid of anyone, because Christian Truth and God stood behind him.

Dialogue between Lefty and the British. Continuation of the story

After a short digression, let’s turn again to the plot, but at the same time let’s not forget the image of Lefty in Leskov’s tale.

The British were so delighted with the work that they demanded that the master be brought to them without hesitating for a second. The king respected the British, equipped Lefty and sent him with an escort to them. In the protagonist's voyage to England there are two important points: conversation with the British (Leskov’s story “Lefty” is perhaps the most interesting in this part) and the fact that, unlike Russians, our ancestors do not clean the barrel of guns with bricks.

Why did the British want to keep Lefty?

The Russian land is full of nuggets, and they are not paid attention to special attention, but in Europe they immediately see “diamonds in the rough.” The English elite, having once looked at Lefty, immediately realized that he was a genius, and the gentlemen decided to keep our man, teach him, clean him up, enrich him, but that was not the case!

Lefty told them that he didn’t want to stay in England, he didn’t want to study algebra, his education—the Gospel and the Half-Dream Book—was enough for him. He doesn't need money, nor women.

It was with difficulty that the left-handed man was persuaded to stay a little longer and look at Western technologies for the production of guns and other things. Our craftsman was of little interest in the latest technologies of that time, but he was very attentive to the storage of old guns. Studying them, Lefty realized: the British do not clean the barrel of their guns with bricks, which makes the guns more reliable in battle.

Despite this discovery, main character Skaz still felt very homesick for his homeland and asked the British to send him home as soon as possible. It was impossible to send by land, because Lefty did not know any languages other than Russian. It was also unsafe to sail on the sea in the fall, because it is restless at this time of year. And yet they equipped Lefty, and he sailed on a ship to the Fatherland.

During the journey, he found himself a drinking buddy, and they drank all the way, but not out of fun, but out of boredom and fear.

How bureaucracy killed a man

When friends from the ship were put ashore in St. Petersburg, the Englishman was sent to where all foreign citizens are supposed to be - to the “messenger house”, and Lefty was sent in an ill state through the bureaucratic circles of hell. They couldn’t admit him to any hospital in the city without documents, except the one where they were taken to die. Moreover, various officials said that Lefty needed to be helped, but here’s the problem: no one is responsible for anything and no one can do anything. So the left-handed man died in a hospital for the poor, and on his lips there was only one phrase: “Tell the Tsar Father that guns cannot be cleaned with bricks.” He nevertheless told it to one of the sovereign’s servants, but it never reached the Almighty. Can you guess why?

That's almost all on the topic “N.S. Leskov “Lefty”, brief content.”

The image of Lefty in Leskov’s tale and the model of the fate of a creative person in Russia

After reading the work of the Russian classic, a conclusion involuntarily arises: a creative, brilliant person simply has no hope of surviving in Russia. He will either be tortured by unchristian bureaucrats, or he will destroy himself from within, and not because he has some unresolved issues, but because Russian people are not able to simply live, his lot is to die, burning up in life like a meteorite in the earth’s atmosphere . This is the contradictory image of Lefty in Leskov’s tale: on the one hand, a genius and a craftsman, and on the other hand, a person with a serious destructive element inside, capable of self-destruction in conditions when you least expect it.

1880s - the heyday of N. S. Leskov’s creativity. He spent his whole life and all his strength trying to create a “positive” type of Russian person. He defended the interests of peasants, defended the interests of workers, denounced careerism and bribery. Looking for positive hero N. S. Leskov often addresses people from among the people. “Lefty” is one of the peaks artistic creativity writer. N. S. Leskov does not give a name to his hero, thereby emphasizing the collective meaning and significance of his character. “Where “Lefty” stands, you should read “Russian people,” the writer said. He loves his hero, but does not idealize him, showing that despite his hard work and skill, he was not trained in science and, instead of the four rules of addition from arithmetic, he takes everything from the Psalter to the Half-Dream Book.

The narration is conducted by a narrator, his speech is full of neologisms. "N. S. Leskov... is a wizard of words, but he did not write plastically, but told stories, and in this art he has no equal,” noted M. Gorky. And it’s hard to disagree with this. That is why N. S. Leskov was constantly looking for “living faces” who had rich spiritual content and could interest others. To do this, N. S. Leskov uses the memoir form of a fictional work of art. “Memoir” is only an artistic means, since most of Leskov’s heroes did not have prototypes.

The language of the story is “real, superfluous Russian”; it required a lot of painstaking work from the author. However, in the story it is perceived simply and clearly. It contains obsolete words (“Aglitsky flea”, “yashcheisky”, “vereta”), vernacular (“rumor”, “trifle”, “kislyarka”, “peppered with hammers”), borrowed words, often distorted (“melancholy”, “melkoskop”, “nymphosoria”, “danse”).

At the end of the story, Pushkin’s statement sounds - “things days gone by" and "legends of antiquity."

The story has the "fabulous texture of a legend" and the "epic character of the protagonist." The real (proper) name of the left-hander is not given; it, like the names of many geniuses, is forever lost to posterity. N. S. Leskov created a myth personified by fantasy.

In the last chapter, the writer regrets that with the development of technology, machines replaced manual labor. Machines, according to the author, “do not favor aristocratic prowess, which sometimes exceeded the limit and inspired folk imagination to compose such fabulous legends as today.” N. S. Leskov shows that workers appreciate the benefits that mechanics provide them, but they remember the old, bygone times with pride and love.

N. S. Leskov himself, assessing artistic originality“Lefties” complains that creating a language is a very labor-intensive task. In his opinion, only love for his work can motivate a person to take up such mosaic work. N. S. Leskov writes: “It was this very “peculiar” language that they blamed me for and finally forced it to spoil and discolor a little.”

“Lefty” is a work in which the writer achieved great strength and depth of artistic generalization. It so accurately recreates the speech color of the depicted environment that when reading the story, the illusion of the authenticity of the events and the reality of the narrator’s image arises.